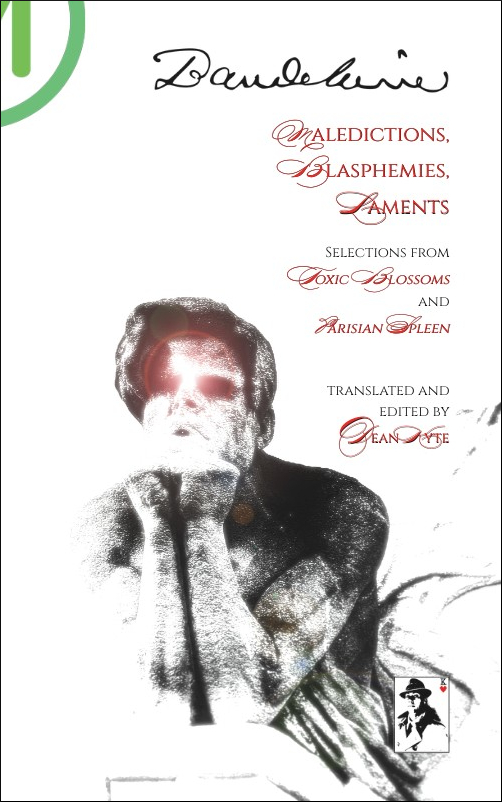

My new book of translations drawn from the works of Charles Baudelaire, Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments: Selections from Toxic Blossoms and Parisian Spleen, is fast coming to press.

And in today’s video on The Melbourne Flâneur, I take you inside the softcover version of the book as I explain—with due reference to Baudelaire—the rationale behind my choice of such a bitter and pitiless title.

As I say in the video, what appears on its face to be a title utterly alienating in its satanic vituperation is in fact the highest possible homage that Baudelaire can render to God’s majesty, and the proof of his most fervent belief, as a heretical Catholic, in the Supreme Being.

Thus, at a plutonic hour of human history where faith in God and human goodness could not be more ridiculous, I too assert, in taking this title, my quixotic faith in what is highest in man by ‘praising with sharp damnation’ what is lowest in our species, we irredeemable children of the tribe of Cain.

For there must no longer be any doubt in our present year, even to the somnambulistic billions who would make ‘the Woman Question’ and ‘the Jewish Question’ of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries suddenly ‘the Human Question’ of the twenty-first, that Baudelaire’s apocalyptic prophecy of modernity—a veritable ‘Age of Iron’—has now properly revealed itself in our day.

The time could not be more right for the apparition of this book.

One hundred twenty-one years to the very day of my birth, Baudelaire writes in his journal that ‘today … I suffered a singular alarm: I felt the wind of the wing of madness pass over me.’

Charles Baudelaire is the Alpha of the dandy-flâneur, the man, in modernity, who still seeks to be a ‘man’—to live heroically in the strength of all our human frailties and the humility of our profound limits—and I am the Omega, the decadent result of two centuries of societal degeneracy in the West, the last quixotic figure, in the armour of my hat and suit, to intransigently ‘hold the faith’ in that utterly discredited, unconscionable project of embodying ‘Homo Occidentalis’ in all his risible nobility.

So, as a mad Aquarian, an avatar of the New, destiny has elected me for a task, chers lecteurs;—to be the ‘postrunner’ of this great fallen angel of modernity, this great albatross of a luciferic intellect who found his wingspan so vast he couldn’t walk easily among us, and interpret to the Anglosphere, as an evangelist after the fact, the poetry and prose poetry of Charles Baudelaire.

And I’m pleased as punch to advise you that Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments is on the verge of seeing the light of day.

I explain the origins of the book’s title in the video above, but here below, I am posting for the first time the line-up of fifty pieces I have selected from Les Fleurs du mal and Le Spleen de Paris to take the field as the Baudelairean ‘dream team’ and represent our poet.

So, here we go…

From Toxic Blossoms (Les Fleurs du mal):

- “To the Reader” (« Au Lecteur »)

From “Spleen and Ideal” (« Spleen et Idéal »):

- “Blessing” (« Bénédiction »)

- “The Albatross” (« L’Albatros »)

- “Elevation” (« Élévation »)

- “Correspondences” (« Correspondances »)

- “The Venal Muse” (« La Muse vénale »)

- “The Faithless Monk” (« Le Mauvais moine »)

- “Illfated” (« Le Guignon »)

- “Past Life” (« La Vie antérieure »)

- “Beauty” (« La Beauté »)

- “The Ideal” (« L’Idéal »)

- “The Giantess” (« La Géante »)

- “The Jewels” (« Les Bijoux »)

- “Hymn to Beauty” (« Hymne à la Beauté »)

- “You’d let all mankind dally in your alley…” (« Tu mettrais l’univers entier dans ta ruelle… »)

- “With her raiment, sinuous and nacreous…” (« Avec ses vêtements ondoyants et nacrés… »)

- “The Possessed” (« Le Possédé »)

- “An Apparition” (« Un Fantôme »)

- “I make a gift of these verses to you so that if my name…” (« Je te donnes ces vers afin qui si mon nom… »)

- “Vespers” (« Chanson d’après-midi »)

- “Spleen” (« Quand le ciel bas et lourd pèse comme un couvercle… »)

- “Warning” (« L’Avertissement »)

From “Parisian scenes” (« Tableaux parisiens »):

- “The Sun” (« Le Soleil »)

- “The Swan” (« Le Cygne »)

- “To a Passerby” (« À une passante »)

- “Evening Twilight” (« Le Crépuscule du soir »)

From “Wine” (« Le Vin »):

- “The Soul of Wine” (« L’Âme du vin »)

From “Toxic Blossoms” (« Les Fleurs du mal »):

- “Epigraph for a Condemned Book” (« Épigraphe pour un livre condamné »)

- “The Two Wellbred Girls” (« Les Deux bonnes sœurs »)

From “Rebellion” (« Révolte »):

- “Litanies of Satan” (« Les Litanies de Satan »)

From “Death” (« La Mort »):

- “A Connoisseur’s Dream” (« Le Rêve d’un curieux »)

- “The Journey” (« Le Voyage »)

I have selected fully one-fifth of the total number of poems published in the three editions of Les Fleurs du mal which Baudelaire, and then his mother, saw through the press.

At least twenty per cent of every section of Les Fleurs du mal is represented in Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments, and because Baudelaire’s poetry collection is a psychological novel with a narrative order, in selecting at least a fifth of the poems from every section, I have taken care to choose those works which I think best highlight the themes of that section and carry the overarching drama forward.

The figure of one-fifth includes the six pieces that were struck from the first edition as obscene, banned in France, and were only subsequently available in Belgium among Les Épaves (1866).

One of the censored poems, « Les Bijoux », is included, and as you can see, that piece, which I published in my first collection of Baudelaire translations, Flowers Red and Black (2013), is listed in orange.

With the exception of « Spleen », the titles in orange are works from the earlier book which are still in the buffer awaiting revision.

As this post goes to press, I am about to start revising « Spleen », which I also translated in the years preceding the publication of Flowers Red and Black but declined to include in that book, so this poem will see the light of day for the first time in Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments.

And the word ‘revise’ in this instance basically means ‘completely rewrite’.

While I was translating Baudelaire’s short story, « La Fanfarlo » between February and April, instead of working on the few remaining poems I have left to translate, I began to revise the pieces from Flowers Red and Black, but in every instance I found myself writing completely new translations of these existing poems.

So it’s going to be interesting when I look at “The Jewels” again in a couple of weeks, because this is by far my most well-known translation of a work by Baudelaire, the piece that often cliched sales of Flowers Red and Black. Is this poem going to run true to form with the rest of the book and am I going to see the text in a whole new light?

What I can tell you for certain is that a revised version of “The Jewels” will include a translation of the newly revealed ninth verse that was discovered in 1928, written in Baudelaire’s hand, in a first edition of Les Fleurs du mal which he gave to a friend but only made public when that copy came up for auction in 2019.

You will also notice that, in the list above, there are three titles in red: « Le Cygne », « Les Litanies de Satan », and « Le Voyage ».

These are the last outstanding selections from Les Fleurs du mal that I am yet to translate. They’re Baudelaire’s most famous poems; they’re among my longest selections, and they’re going to be the greatest tests of my interpretative abilities.

So that’s Les Fleurs du mal. Now let’s look at what you can expect to read from Le Spleen de Paris.

From Parisian Spleen (Le Spleen de Paris):

- “To Arsène Houssaye” ( « À Arsène Houssaye »)

- “The Stranger” (« L’Étranger »)

- “The Artist’s Confiteor” (« Le Confiteor de l’artiste »)

- “A Troll” (« Un plaisant »)

- “Twin Suite” (« La Chambre double »)

- “The Buffoon and the Venus” (« Le Fou et la Vénus »)

- “At an Hour after Midnight” ( « À une heure de matin »)

- “Crowds” (« Les Foules »)

- “Invitation to the Journey” (« L’Invitation au voyage »)

- “Hungry Eyes” (« Les Yeux des pauvres »)

- “The Magnanimous Gambler” (« Le Joueur généreux »)

- “Sozzle Yourself” (« Enivrez-vous »)

- “Windows” (« Les Fenêtres »)

- “The Port” (« Le Port »)

- “Lost Halo” (« Perte d’auréole »)

- “Anywhere Out of the World ” (« N’importe où hors du monde »)

- “Epilogue” (« Épilogue »)

One-third of the total number of pieces from Le Spleen de Paris will be featured in Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments, including Baudelaire’s prefatory letter to Arsène Houssaye—which ought to be considered a prose poem in its own right—and the poem that Baudelaire appends as epilogue to the collection.

I was convinced that these two pieces—which I had no previous intention of translating—needed to be included when I was in Brisbane in December. Reading Sonya Stephens’ insightful little book Baudelaire’s Prose Poems: The Practice and Politics of Irony (2000) at the State Library of Queensland convinced me that these were inescapable framing texts.

And you’ll notice we have one text in red: « Le Port ». After I complete the revision of « Spleen », that short, pretty little prose poem is next on my list.

So, if you’ve been keeping count, chers lecteurs, you’ve clocked 49 pieces and I promised you fifty. What’s the big 5-0?

“Fanfarlo” (« La Fanfarlo »)

The translation of Charles Baudelaire’s only known original short story is now complete.

The longest, most ambitious translating project I’ve undertaken in any language was completed to my satisfaction at the end of last month after 134 hours and seven drafts of work.

A task I approached with trepidation and misgivings, thinking I would be merely giving the reader a ‘bonus’ text that was still going to cost me time and sweat, I now believe to be one of the major selling points of Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments.

One of the reasons I think this version of « La Fanfarlo » will last for quite a long time as an introduction to what is, for English readers, an overlooked part of Baudelaire’s œuvre is my decision to include footnotes to the text.

I found that there were three types of instance where a footnote would aid the reader’s understanding, the most important being the occasional footnote that takes you inside my process as a translator, shows you clearly what the French is and how it can be variously interpreted, and what ultimately informed the choice I’ve gone with in the text based on my intimacy with Baudelaire’s typical modes of thinking and expression.

So, 86 per cent of the poems, prose poems—and fiction—of Charles Baudelaire that you will shortly be reading in Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments is now locked in.

And this week, apace with my final revisions and translations, I pulled out my trusty essay plan and began plugging in points and sources for the last remaining major task before this book goes to print:—my contribution, an 8,000-word critical monograph on Baudelaire that I hope will serve to honourably introduce the man, the myth, the œuvre to the English-speaking world.

What I’ve written about Baudelaire on The Melbourne Flâneur, I’ve written off the cuff.

But what I write in the critical monograph introducing Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments, I intend to be my definitive statement on Baudelaire—at least for the next ten years, when I will have doubtless more translations of his work to offer the English-speaking world.

When I published Flowers Red and Black in 2013, I had no idea that people would see such a close connection between Baudelaire and myself, as parallel lives across centuries, souls who cannot take quiet desperation.

I am truly the ‘mon semblable, mon frère’ (‘my double, my brother’) whom he salutes in the last line of the very first poem of Les Fleurs du mal, « Au Lecteur »—a fraternal spirit of revolt.

What I say about Baudelaire in the critical monograph will be the fruit of some seventeen years of working intimately with the thoughts of a literary mind that is as much a black mirror to my own as Edgar Allan Poe’s was to Baudelaire’s.

And I intend it to stand the test of future times and tastes as Baudelaire’s critical essays on Poe have proven their lasting value as perspicacious insights into that poor unfortunate’s life and work from a fraternal spirit who knew the horror he was experiencing only too well.

I am now taking pre-orders for Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments, and I invite you to get onboard now.

The price point I am looking at for the softcover version advertised in the video above is $A32.00, exclusive of shipping.

(For my American readers, that’s approximately $20.50 in your yanquí dinero.)

For that price, you’re going to receive:

- A 180-page illustrated softcover edition with pages printed in full colour

- Autographed and wax-sealed by me as a guarantee of authenticity

- Handwritten, personalised inscription from me to you

- Complementary custom bookmark

My proposal to you is to purchase now to guarantee your copy at that price point in the initial print run, and after I go to print, I will invoice you for shipping.

And by pre-ordering, you will also join the community of consumers who have already committed to purchase Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments. I’m sending emails on a monthly basis to my readers, staying accountable by keeping them up to date with my progress towards publication—and taking them inside my Artisanal Desktop Publishing process, the joys and vagaries of writing, designing and publishing this book with exclusive content not posted here on The Melbourne Flâneur.

So, avail yourself of the order form below and book your ticket to Cythera on the Baudelaire boat.

“Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments” [softcover]

Personally signed, sealed and inscribed by author. Comes with custom bookmark. Pre-order your copy and join an exclusive community of readers anticipating the release of Dean Kyte’s new book!

A$32.00