Sons et paroles, couleurs et formes, le visible surtout, ne sont pourtant que des symboles de l’idée, symboles qui naissent dans l’âme de l’artiste quand il est agité par le saint-esprit du monde; ses œuvres ne sont que des symboles à l’aide desquels il communique aux autres âmes ses propres idées.

Sounds and words, colours and shapes—above all, the visible—are, nevertheless, merely symbols of the idea, symbols that arise in the artist’s soul when he is shaken by the holy spirit of the world. His works are but symbols through whose aid he communicates his own ideas to other souls.

— Heinrich Heine, « Le Salon de 1831 », De la France (1867, pp. 346-7 [my translation])

In “Heine and the French Symbolists” (1978), Haskell M. Block demonstrates that it was the German poet Heinrich Heine, who had settled in Paris in 1831, who introduced into French poetic thought a notion that was then prevalent in German Romanticism.

The idea of a fundamental and unitary correspondence between sense phenomena such as sound, scent and colour would have profound ramifications for the development of French prosody in the nineteenth century, influencing the poet whom Charles Baudelaire would hail, in the dedicatory device prefacing Les Fleurs du mal, as the ‘perfect magician in the field of French letters’, Théophile Gautier, and subsequently Baudelaire himself.

Heine, a melancholic yet ironic poet, would die in Paris in 1856, the year before the publication of the first edition of Les Fleurs du mal. In tracing the extent of Heine’s influence on French poets throughout the century, Block shows that Baudelaire had read deeply in Heine’s poetry and prose, and the correspondences in style and outlook between the older German poet and his younger French contemporary are striking, the more so because, as Block says, ‘despite these affinities, Heine is not a major force in shaping Baudelaire’s poetics or poetry.’

He did, however, influence Baudelaire’s æsthetics and, along with Diderot, Heine would provide Baudelaire with a model on which to base his reviews of the Salon exhibitions of 1845 and 1846. In the latter, Baudelaire cites directly from Heine’s review of the 1831 exhibition, substituting the name of his own artistic hero, Eugène Delacroix, for that of the Orientalist Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, as a more convincing proof of Heine’s theory of correspondences:

En fait d’art, je suis surnaturaliste. Je crois que l’artiste ne peut trouver dans la nature tous ses types, mais que les plus remarquables lui sont révélés dans son âme comme la symbolique innée d’idées innées et au même instant.

In matters of art, I am a supernaturalist. I believe that the artist cannot find all his models in nature, but that the most remarkable are revealed to him in his soul simultaneously as the innate image of innate ideas.

— Heine (1867, p. 349 [my translation])

But as Block explains, this Germanic theory of a precise correspondence between the platonic Idea and the actual form that it takes in nature, symbolic of itself, was more philosophical than mystical, owing more to the speculations of Kant than to those of Swedenborg.

For the German Romantics, imagistic symbols had more of a psychological character than an esoteric one.

In appropriating this German Romantic philosophical idea that Heine had imported into France and superimposing it upon the artistic temper and process of France’s foremost contributor to the Romantic movement, Baudelaire would conflate the intellectual conception of a poetic correspondence between the phenomena of nature with the æsthetic supernaturalism to which Heine claimed to be an adherent.

From his hero Delacroix, Baudelaire would imbibe the belief, as expressed in his sonnet “Correspondances”, the most powerfully compressed æsthetic manifesto of the French nineteenth century, that nature—the sensual world that actually surrounds us—is nothing more or less than a ‘dictionnaire hiéroglyphique’, whose signs, as Richard Sieburth says in Late Fragments (2022), ‘always pointed elsewhere or beyond.’

In this sense of the ‘real’, Baudelaire was, like Heine, a ‘supernaturalist’ in artistic matters, one who sought the holy-spiritual model that is over and above an object’s manifestation in nature.

But Baudelaire goes further than Heine and the philosophically-inclined Germans.

If the magickal grimoire of the alchemists is simply, etymologically, a grammar, a book that sets forth the precise syntax and morphology of the Logos such that, when the Word of God is correctly pronounced and articulated, it will call forth invisible spirits latent in the natural, then the ‘hieroglyphical dictionary’ of visible nature is correspondent with the invisible Verbe—the Holy Word (and thus Christ as the Word made flesh)—that is consubstantial with the signs and symbols of the sensual phenomena that daily surround us.

Baudelaire had developed this notion from his readings of the scientist and Christian mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg, who, unlike Heine, would indeed be a ‘major force’ in shaping his poetics, as the sonnet “Correspondances” makes clear.

In addition, it is known that Baudelaire was familiar with the work of his elder contemporary Alphonse-Louis Constant, a former priest, an occasional poet and socialist literary man-about-Paris in the febrile years leading up to the fall of the July Monarchy, and better known to posterity as an occultist under the name he would take after the rise to power of Napoleon III, Eliphas Lévi.

Lévi, as Jon Leaver explains in an endnote to his article “‘Sorcellerie évocatoire’: Magic and Memory in Baudelaire and Eliphas Lévi” (2012), had also published a poem entitled “Correspondances” in his collection Les Trois harmonies (1845).

Leaver cites two instances of similar poetic ideas emerging from Lévi’s phraseology, but concludes that, despite some superficial similarities, it is ‘actually unhelpful’ to seek a source for Baudelaire’s sonnet in the elder man’s poem. I agree that, from the examples cited, Lévi’s concept of correspondence between man and nature appears to be less sophisticated than the immensely compressed, highly elliptical, and yet cosmically telescopic thesis Baudelaire presents as the very basis of his æsthetic credo in Les Fleurs du mal.

It is unknown whether Baudelaire had read the poem or even if he had met Lévi, despite both poets moving in the same Fourierist circles. However, in a footnote to the poem “L’Imprévu”, published in the late, abortive collection Les Épaves (1866), Baudelaire recommends to the reader Lévi’s Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (1854-6) as a secondary source on ‘sorcery, demonology, and satanic ritual’ useful to interpretation of the poem.

L’analogie est le seul médiateur possible entre le visible et l’invisible, entre le fini et l’infini. …

[L]’analogie est le quintessence de la pierre philosophale, c’est le secret du mouvement perpétuel, c’est la quadrature du cercle, … c’est la racine de l’arbre de vie, c’est la science du bien et du mal.

Analogy is the only possible intercessor between the visible and the invisible, between the finite and the infinite. …

[A]nalogy is the quintessence of the Philosopher’s Stone; it is the secret of perpetual motion and the squaring of the circle; … it’s the root of the Tree of Life and the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

— Eliphas Lévi, Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (2008, pp. 215, 217 [my translation])

Thus, the essence of poetry itself—the operation of likening two disparate things via the correspondence of analogy—is, as Lévi explains, a fundamentally alchemical operation that calls forth from the visible and bounded the invisible and the infinite.

Séparer le subtil de l’épais, dans la première opération, qui est tout intérieure, c’est affranchir son âme de tout préjugé et de tout vice : ce qui se fait par l’usage du sel philosophique, c’est-à-dire de la sagesse ; du mercure, c’est-à-dire de l’habileté personnelle et du travail ; puis enfin du soufre, qui représente l’énergie vitale et la chaleur de la volonté. On arrive par ce moyen à changer en or spirituel les choses même les moins précieuses, et jusqu’aux immondices de la terre. C’est en ce sens qu’il faut entendre les paraboles de la tourbe des philosophes … et des autres prophètes de l’alchimie ; mais dans leurs œuvres, comme dans le grand œuvre, il faut séparer habilement le subtil de l’épais, le mystique du positif, l’allégorie de la théorie. Si on veut les lire avec plaisir et avec intelligence, il faut d’abord les entendre allégoriquement dans leur entier, puis descendre des allégories aux réalités par la voie des correspondances ou analogies indiquées dans le dogme unique :

Ce qui est en haut est comme ce qui est en bas, et réciproquement.

To divide the etheric from the carnal, in the first operation—which is entirely internal—is to liberate the soul of every prejudice and vice. This is accomplished through the employment of philosophical salt, which is to say, wisdom; through mercury, which is personal skill and labour; then, finally, through sulfur, which represents vital energy and the fervour of the will. By this process, one attains the ability to transform even the least precious things—right down to the filth of the earth—into spiritual gold. It is in this sense that one must understand the allegories of sod spoken of by the philosophers … and other prophets of alchemy. Yet in their works, as in the Magnum Opus, it is necessary to adroitly divide the subtle from the gross, the mystical from the scientific, the allegorical from the theoretic. If we desire to read these works with satisfaction and discernment, we must first understand them allegorically in their entirety, then descend from that level to concrete realities along the path of correspondences or analogies indicated in the only dogma:

As above so below, and vice versa.

— Lévi (2008, p. 152 [my translation])

Even in the disenchanted world of modernity, the objects of our actuality double as the signs of the inexpressible definitions in eternity that they refer to.

And thus, in taking for his hieroglyphic dictionary the unpoetic realm of the urban real, Baudelaire’s alchemical praxis as the first poet of modern life is a proto-noir ‘expressionism’ of what he had gathered, via Heine, from the earlier generation of German Romantics. His is the first form of a ‘réalisme poétique’.

As Alain Robbe-Grillet puts it, before being ‘something’—something that is graspable by and meaningful for human comprehension—objects are simply there—là.

And before this implacable ‘there-ness’, this ‘là-ness’, according to Max Nordau, the degenerate feels mystified and plagued by doubts as to the unsearchable first causes of this implacable reality. ‘He is ever supplying new recruits to the army of … seekers for the philosopher’s stone, the squaring of the circle and perpetual motion’—the very problems that, according to Lévi, are solved by the alchemical operation of analogy, by the Baudelairean principle of poetic correspondence.

In Nordau’s account of poetic and artistic degeneration under the conditions of scientific, capitalistic, technological modernity, the good doctor can see no place for the poet, at least insofar as he occupies the traditional rôle he has played in all pre-Cultural societies—that of the priest, the prophet, the shaman, the man who, as I say in my translation of Baudelaire’s “Correspondances” above, ‘traverses this hierophantic grove of glyphs’, bridging, integrating the two hemispheres of the brain, the discreet, rational domain governed by Logos, and the holistic realm of perceived correspondences high and low, between all phenomena, presided over by Imago.

Baudelaire, as what Dr. Raymond Trial called ‘the typical superior degenerate’, is the cream and the crest of Western Civilization, a late-born member of the first generation to live under the declining ‘nouveau régime’ of Western modernity.

And as—(by comparison to ourselves)—the most healthy specimen of this type of ‘superior degenerate’, as an intransigent résistant, a Romantic revolter, an anti-Nietzschean naysayer to the liberal shibboleths of infinite scientific and social progress, Baudelaire finds himself left out of Nordau’s account of a ‘sane’—which is to say, etymologically, ‘healthy’—poetry.

Instead, he is the fountainhead, for Nordau, of the insane in poetry—the ‘malsain’.

In this rigidly rational, positivist régime that has driven us all, over the last two and a quarter centuries, to experience the crucible of paralyzing hysteria that Baudelaire was among the first to go through, we have seen how little place there is for poetry in the modern world, how little poetry there seems to be in the sensual phenomena of our actuality.

Yet from this bleak and noirish facticity, the unprepossessing ‘thereness’ of the inescapably ugly urban environment—‘the filth of the earth’, as Lévi calls it—Baudelaire discovered in the miasma of his Parisian reality the incantatory magick, the ‘evocative sorcery’, as he would call it, of the Verbe-made-flesh, of the indexical sign consubstantial with its correspondent referent in eternity, and thus the spell of rhythm and rhyme as the essential operation that transformed the base dross of his splenetic actuality into the incorruptible gold of an Ideal whose image is still chanted through the French-speaking world.

In Les Fleurs du mal, Baudelaire seeks to reclaim the pre-Cultural rôle of the poet as shaman, as witchdoctor, the esoteric alchemist of a society disenchanted by Luciferic positive science, the benighted mage who distils the healing quintessence from the poisonous herbarium of correspondent, actual nature that he gathers in the grimoire of his collection’s pages.

The built, lapidary environment of Baudelaire’s actual ‘nature’ is an utterly novel environment for Western man to attempt to colonize and thrive in. The Parisian megalopolis, the renovated Rome of the Civilized West, the Benjaminian ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’ stretching forth the tentacles of its cultural imperium of taste under the auspices of Napoleon III even to the antipodes of Melbourne, was a technological marvel of good living—a veritable ‘machine à vivre’—such as had never been seen before.

From hysterical Paris, fatigued, according to Nordau, by the general nervous exhaustion brought on by an unremitting tumult of frenzied revolution—political, cultural, artistic—modernity’s chief mechanism of mimetic propagation, fashion—the famous Paris fashion, desired by all the world—broadcast itself to the whole Occidental diaspora as le dernier cri in how to live comme il faut.

Benjamin quotes the Decadent and Symbolist poet Jules Laforgue as saying that Baudelaire was the first to speak of Paris ‘as someone condemned to live in the capital day after day.’ To be where all the world wants to be was, for this native-born Parisian, to be in ‘hell’, and Baudelaire baldly calls Paris by that name in his correspondence.

He is at the vanguard, on the barricades of this agonistic encounter with a ‘new nature’, mineral rather than vegetable, technological rather than magickal, artificial and spectacular rather than organic and authentic, that we have long regarded as our ‘new normal’.

The Paris of the mid-nineteenth-century—which is still the Paris of today—is necessarily an alienating environment. The medieval ‘forêt de symboles’ that Baudelaire had traversed in his youth falls beneath the ram and blow of Baron Haussmann’s renovations to be replaced by the new, geometric, astral order that we recognize today, a Lapis of glass, marble, macadam, iron and asphalt.

Even the Manhattan of Baudelaire’s transatlantic contemporary, Walt Whitman, is still rustic and provincial, and as yet nothing to compare, in world-historical terms, with the technological Babel of new hieroglyphs mutating daily around the islands of the Seine.

Everything Baudelaire beholds in his flâneries through the capital, practising, with diffuse attention, his ‘fantasque escrime’, speaks obscurely—‘de confuses paroles’— of the portentous future we now recognize as our globalized present. To capture, by a correspondent language, the ephemerality of the actual in this flux of mutating impressions that the cataract of fashion pushes past one’s eyes into the abyss of the past is to disengage what is eternal about these transitory phenomena.

In pre-Cultural social organizations, the medicine man, according to Michel Bounan, embodies, for his community, the rôle of the ‘universal living subject’—man in his correspondent relationship to the cosmos, something like Lévi’s vision.

The poet in scientistic modernity, finding his gnostic, shamanistic rôle deprecated by ‘the market’, that volatile, atomized, democratic entity which replaces the embodied ‘church’ of the community, now finds himself suddenly rendered impotent, stripped of the magickal powers that his prestigious command of the Verbe once invested him with, and alienated from this materialistic order deracinated from the eternal ground of Spirit.

In this brave, new, ‘re-cruded’ world of fungible commodities, the poem, that abstract, conceptual artwork with its roots plunged deeply in the purely oral pre-Culture of Western man’s infancy, as invocatory prayer to God and celebratory praise of the hero, must make a further leap beyond the technological revolution of writing.

In Baudelaire’s time, the press, that Gutenbergian innovation upon written language which, in the eighteenth century, had roused, stoked and maintained the sanguinary inferno of the Revolution, had, by the mid-nineteenth century, made the word as gross a journalistic commodity as the more tangible materials that supported Parisian life—coffee, chocolate, precious metals, iron and textiles.

From his early period on, he viewed the literary market without any illusions. In 1846 he wrote: ‘No matter how beautiful a house may be, it is primarily, and before one dwells on its beauty, so-and-so many meters high and so-and-so many meters long. In the same way, literature, which constitutes the most inestimable substance, is primarily a matter of filling up lines; and a literary architect whose mere name does not guarantee a profit must sell at any price.’ Until his dying day, Baudelaire had little status in the literary marketplace.

— Walter Benjamin, “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire”, The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (2006, p. 65)

In the marketplace of newspapers, reviews, and publishing houses of Paris, where he was, for owners, editors and printers alike, a frequent nuisance and encumbrance, Baudelaire, already alienated from this progressive order of laissez-faire trade, must sell his wares, these magickal words that remain the high-water mark of correct usage in modern French, as base articles of merchandise ‘by the gross’.

Baudelaire must do this, moreover, going cap in hand to the bourgeois ‘traders in words’, virtually begging them to print poems that, by the end of the century, will be regarded as among the immortal articulations of the language, on the lowest terms, for the meanest means of his subsistence, while simultaneously committing himself in hope and faith to the pre-enlightened Magnum Opus of reconstituting the magick Verbe, the Lapis Philosophorum, in an outré prosody that the journalists of the day regard as virtually worthless.

… [L]e grand oeuvre est quelque chose de plus qu’une opération chimique : c’est une véritable création du verbe humain initié à la puissance du verbe de Dieu même.

… [T]he Magnum Opus is something greater than a chemical operation: it is a veritable creation of human Logos initiated into the power of the very Word of God.

— Lévi (2008, p. 316 [my translation])

As Marc Eigeldinger explains in his article “Baudelaire et l’alchimie verbale” (1971), in one of its dual aspects, the alchemical process involves a conquest of temporality via the operatio of transmuting the base and corrupted world of matter. In its other aspect, it is the effort to revalorize the Word, to reimbue it with its sacred quality, and to quarry from its correspondent hieroglyphs in material nature a symbolic—which is to say, poetic—language buried in the dross of our fallen world.

In his article, Eigeldinger cites a letter that Baudelaire wrote to Alphonse Toussenel in January 1856. There, he goes exoterically further than he does in “Correspondances”, explicitly stating his belief to the naturalist and journalist that ‘la Nature est un verbe, une allégorie, un moule, une repoussé — Nature is a language, an allegory, a mold, a matrix’.

It is thus the case that the act of literary translation is an act of alchemical transmutation: Baudelaire’s unremunerative labour to decipher the hieroglyphical dictionary that is the modern environment of Paris, converting the ensouled symbology of the megalopolis’s ‘piliers vivants’ into the incorruptible, abstract artifacts of poems that correspond precisely and eternally with these material symbols’ ephemeral actuality, is an esoteric operation upon himself.

It is the attempt to revalorize his miserable existence of an all-too-brief moment, some 46 years of poverty and illness, loneliness and salutary madness that seem to him an eternal and infinite hell.

He was not to leave for Hell so soon. Catulle Mendès chanced to meet him at the Gare du Nord: shabby, sullen, almost menacing. He explained that he had come to Paris on business, and that he was going back to Brussels, but that he had missed the evening train. Mendès lived near the station, in the rue de Douai. He offered him a bed for the night. Baudelaire accepted the offer.

In the rue de Douai, he stretched himself out, fully dressed, on the sofa, asked for a book, and began to read. Suddenly he dropped the book, and asked: ‘Do you know, mon enfant, how much money I have earned since I began to work, since I was born?’

‘There was in his voice a heartrending bitterness of reproach and, as it were, of protest. I shuddered [Mendès remembered]. “I don’t know,” I said. “I’m going to count it out to you,” he cried. And his voice grew exasperated as if with rage … He listed, with their payments, the articles, the poems, the prose poems, the translations, the re-publications, and, adding them all up, in his head, … he announced: “The total profits of my whole life: fifteen thousand eight hundred and ninety-two francs and sixty centimes!” He added, with chattering teeth: “Note those sixty centimes—two Havana cigars!”’

Jacques Crépet was later to calculate that Baudelaire had earned 10,000 francs; Claude Pichois and Jean Ziegler were to put the sum at 9,900 francs.

On that summer night in Paris, in 1865, Mendès’ increasing sadness turned to anger:

‘I thought of the famous novelists, the prolific melodramatists, and … I thought of this great poet, this strange and delicate thinker, this perfect artist who, in twenty-six years of laborious existence, had earned about one franc seventy centimes a day.’

— Joanna Richardson, Baudelaire (1994, pp. 424-5)

In a proposed, unfinished epilogue intended for the second edition of Les Fleurs du mal, Baudelaire drafted two lines that have become the most cited lines in the language as they express the intention behind his alchemical poetic art: ‘Car j’ai de chaque chose extrait la quintessence, | Tu m’as donné ta boue et j’en ai fait de l’or — For, out of all things I have drawn forth the quintessence: | Alms of mud have you made me, and I’ve made gold from the putrescence’ [my translation].

Baudelaire transcends his impotent alienation from the means of industrial literary production that is enjoined upon him as a condition of living in materialistic modernity. But he is torn between the higher, esoteric sorcery of his craft and the crude demands of capitalism, the need, like that of the prostitutes he venerates, to ‘harvest gold from his celestial coffers’.

If, as I argue, Les Fleurs du mal should be understood as an alchemical tract, as a record of Baudelaire’s Faustian quest for the Lapis and the Elixir that will make modern urban life bearable, the most depressing critical realization is that, under the diabolical tyranny of capital, the inestimable gold he has fashioned as one of the great patrimonies of world literature, at the ultimate price of his life and soul, is a result of the unholy act of transmutation that the alchemists of old warn against:—the attempt by Baudelaire to make his leaden life into the mere filthy lucre he needed to survive it.

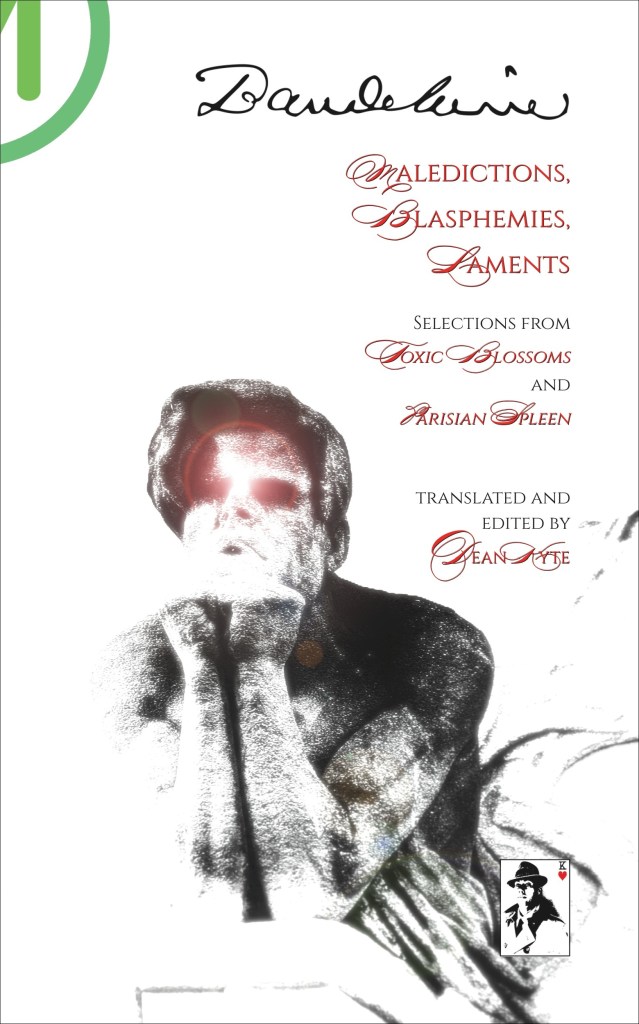

You’ve just been reading the first draft of a ‘chapterlet’ from the critical monograph on Baudelaire which will form the introduction to my forthcoming book of translations of Baudelaire’s poems and prose poems, Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments: Selections from Toxic Blossoms & Parisian Spleen.

All 51 pieces in the book—33 poems, 17 prose poems, and 1 short story—are now complete.

As I put the final touches to the book, my last task is to complete a 10,000-word critical monograph on Charles Baudelaire in which I explain how, in his life and work, he both prophesies and embodies the decadence, decline, and degeneration of modern man that we are now experiencing all throughout the West—and particularly in the Anglosphere.

Pre-order your copy using the links below.