As Coronavirus restrictions ease, today on The Melbourne Flâneur, I get out and about for the first time in two months, taking a flânerie to Bacchus Marsh.

Don’t be deceived by the boggy name: Bacchus Marsh is actually quite a nice place to visit, particularly at the start of winter, when all the trees along Grant street, leading from the station to the township, set up an arcade of red and yellow leaves for you to amble under.

At Maddingley Park, I take a breather at the rotunda to share with you a sneak preview of the manuscript for my next book—a 31-page handwritten letter to my seven-year-old niece, which I wrote during lockdown.

As soon as things got too hairy on the streets, your Melbourne Flâneur, that aristocrat of the gutter, folded up pack, shack and stack and got his handmade Italian brogues parked in more private and stable accommodation than he is used to treating himself to.

For two months, I was sequestered in a West Melbourne hotel room, my world reduced to a single window looking out on a narrow sliver of upper King street. If I crowded into the left side of the window and craned my neck, I could entertain myself by trying to work out on what streets all the tall buildings in the Melbourne CBD were planted.

To say (as I do in the video) that I felt like I was in a ‘gilded prison’ is not to deprecate the kind folks at the Miami Hotel, who I’m very happy to recommend to any visitors to our fair city, but rather to suggest what a strange and vivid time it was to be a writer of a peripatetic persuasion, one who finds his home in the crowd.

In Australia, in the early days of the lockdown, we saw scenes of people returning from overseas being bundled and bullied into suites at Crown, on the government’s tab, and exercising, like les bons bourgeois that they are, their privilege to grouse on Instagram that their confinement in palatial conditions was not up to scratch.

These people enjoyed little sympathy from me. As a writer, the argument that such palatial prison conditions were doing a permanent injury to their mental health cut no ice. Rather, if the mental health of people forced to enjoy such self-isolation at Her Majesty’s expense deteriorates, it is evidence of how little developed are the mental resources of a chattering class to whom every ease and privilege is given in a society that clamours after more and more leisure aided and abetted by technology.

Harsh words, I’ll admit, but as a writer, I found my more modest confinement at the Miami a unique historical privilege which reconnected me with the ancient heritage of my craft and profession.

As soon as I was undercover, as those of you who followed my commentary on the Coronavirus crisis know, fearing the worst, I went straight to work and tried to scratch out every idea and cobble together every piece of research I could find in an effort to make good sense of what the continental was going on outside my little room.

For reasons of historical precedent I’ll explain, I felt—and feel—that the moral responsibility of the writer in a time of crisis is to throw the skills of his profession at the task of collective sensemaking.

And so, while my confrères at Crown faffed and fapped on Facebook and engaged in other acts of mental masturbation with their mobiles, I wrote.

And in fact, apart from penning six long articles on the Coronavirus (which, collectively, could constitute a book on their own), I wrote an entire book—five drafts in two months—for my little niece, attempting to explain the situation to her.

The fifth and final draft takes the form of a 31-page handwritten letter to my niece. It took 25 hours to write, and you can see in the video what the entire manuscript looks like. When spread out in three rows across a table capable of comfortably seating eight people, the manuscript is still wider than the tabletop.

It was an extraordinary experience to ‘write a book by hand’. I thought, when I sat down to handwrite the final draft, that it was simply going to be a ‘copy job’, that I was not going to add anything new or creative to what I had worked up in the previous four drafts.

But when I got in front of the first page of my personalised stationery, when I had my two Montblanc Noblesse fountain pens (one filled with Mystery Black, the other with Corn Poppy Red ink) primed, the experience of committing myself to the words I intended to publish felt like no other book I have written.

Suddenly, the page became a ‘stage’ for me. I was on the stage, and this was the performance. The four previous drafts were mere ‘rehearsals’ for the Big Night, and having learnt my ‘script’, I felt free to improvise upon it, to add and change things as I spontaneously wrote the message of hope and support I intended to communicate to my niece.

Sometimes my eyes even filled with tears as I wrote.

If you know what a ‘Flaubertian’ writer I am, how much I bleed to get a single word onto the page that I am even provisionally satisfied with, you can imagine what an experience it is to write a book that is a ‘spontaneous performance’, where the words I ultimately committed myself to as the words I intended to say for all time to my niece about the Coronavirus, about the rôle of technology in human development, about the future of her generation, were as ‘humanly imperfect’ as only the words of a handwritten letter can be.

If you’re intrigued to know what I had to say to my niece, I give you a sample of the first few pages in the video above.

And it’s not simply the fact that the ‘spontaneity’ of a handwritten letter gives the book a sense of the ‘humanly imperfect’;—it’s in the fact of writing the text by hand itself.

It’s hard to remember, at our technological remove, that for most of human history, most writers have actually written—by hand. No typewriters, and certainly no computers. Truman Capote’s disparaging remark of Jack Kerouac—‘That’s not writing; that’s just typing’—could, regrettably, be applied to most so-called ‘writers’ of the 20th and 21st centuries.

This isn’t merely an élitist distinction. There’s a qualitatively different experience to writing a complex work by hand. The genius-level cognitive co-ordination of hand, eye and brain that James Joyce and Marcel Proust enjoyed would not have produced the greatest novels of the 20th century if these gents had been trained to peck out their thoughts—even at the touch-typist level of virtuosity—rather than guide a fountain pen fluidly across a page.

Moreover, I don’t think it’s coincidental that James Ellroy, who I regard as the greatest living writer, works a mano, has never used a computer, and reportedly doesn’t own a mobile phone. This is a man who eschews distraction and espouses deep focus. The density of his plotting and the inventiveness of his language are testaments to the profound cognitive relationship between writing by hand and the capacity to compass complexity through the abstract symbology of written language.

And though I often get compliments on my handwriting, when I look in awe at the handsome copperplate of some 18th- and 19th-century writers, so perfect-seeming and consistent as to appear to be machine-etched, I feel like the Queensland Modern Cursive of the words I have committed to the page for all time in this book are less ‘elegant’ than I should have liked my niece to read.

But, en revanche, writing a book where the final printed text will be ‘by my own hand’—in the most literal sense—gave me a feeling of reconnecting to the ancient art of my profession—dating back to those scribes whose elegant calligraphy has communicated such ancient books as Genji Monogatari down through ten centuries to us.

We’re too acclimatized to the profound revolution in writing which Gutenberg’s invention of movable type opened up for us nearly 600 years ago. We don’t remember that most books—the Bible or Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry—were handwritten, illuminated manuscripts. Our over-familiarity with type and font, the uniformity of letters and ‘standardization’ of print, has fundamentally changed the nature of what we mean, in the 21st century, by the word ‘writing’, forgetting that machine-printed words are not, as Truman Capote observed, writing at all (in the sense of creative human agency), but typing.

And so, although my handwriting in this book is less than consistent from first page to last, the letters being less ‘uniform’ and ‘standard’ than we are used to expect in a book made since Gutenberg’s time, I quite like the notion of having written a book for my niece which I hope will have the feel of an illuminated manuscript, like an ancient spiritual text, something that connects her, in this hour of crisis for humanity, with all the crises the generations of humanity have endured before her.

For it’s equally hard to remember, let alone imagine, in the 21st century, that most human beings have not known how to read or to write. The profession of ‘scribe’ has always been a noble one—at least until the failed experiment of universal education depreciated it.

If any subtle message might be shaken out of the long articles I wrote on the Coronavirus during lockdown, perhaps it is the conviction that, in the most educated era that humanity has never known, this unnecessary débâcle could—and should—have been avoided. That it wasn’t can be laid squarely at the feet of universal education, which has manifestly failed to realize its promise of making each successive generation more intelligent and engaged with the world than the last.

When you master written language, your capacity to verbally reason, to accurately perceive and interpret the pattern within chaotic events, is increased. If you can write, if you can corral your thoughts in words, you become profoundly dangerous.

Is it any wonder that writers are always the first folks to be housed in the hoosegow when some authoritarian jefe comes to power?

It’s for this reason that the art of the scribe was kept out of the paws of the plebs for so many centuries. To write—to really write—is to think, and I look with disgust—for my niece’s sake—upon a world where people are increasingly put through sixteen to twenty years of formal education and yet are still peasants in their thinking, giving no more evidence of being able to marshal and master their thoughts in a coherent, complex, logical argument than our magickal-thinking forebears.

As I say to my niece in the book, we are no more ‘advanced’ than our earliest ancestors. It is simply that we are habituated to more complicated conditions of life.

The lockdown was a period when it was easy—too easy—for people to succumb to boredom and ennui, to indulge digitally in the lassitude and laziness which is the Shadow of our speed-mad species. Prey to ‘the vultures of the mind’, undistracted by our manifold distractions, and oppressed by the very leisure that we clamour for, most people probably tried to drown themselves all the more in the delusive fakery and shallow abyss of screens during their ‘holiday from life’.

But—thank God—I am a writer, which means I was not wigged out at being locked in a hotel room with only my thoughts for company for two months. Like William Blake, through my self-isolation I had mental health and mental wealth to sustain me. Instead of seeking distraction, I was able to pour out the very resources of thought as ink onto paper.

Most writers, I realized as I stood at my window, looking, it seemed, at an invisible tempest swirling through the streets of Melbourne, have lived in times of profound chaos and unrest. The privilege of education, the noble calling of their profession, enjoins upon them the moral responsibility to be ‘a witness to chaos’.

Whether natural disasters have disrupted the times they live in, or whether their societies have undergone enormous upheavals due to war or political division, the writer is the ‘journalist’, the faithful witness and reporter on ‘what life was like’ at these moments of history.

If you can write, by which I mean, if you can really think; if you have mastered, through the long apprenticeship of education, the abstract symbology of written language to the point where you can make dexterous calculations in the algebra of verbal reasoning, you cannot stand idly by at these moments, but the capacity to think, to reason, to explore ideas through language, and ultimately to shed some clarity on chaos by writing down the formula, the pattern of order you perceive in the disorder swirling all around you, is a moral mission arising from the competency of your professional cognitive skills.

As I stood at the window of my cell, I felt connected, in some spiritual way, with some of the great writers of history whose lives have passed in the midst of chaos. Somehow their handwritten words have survived earthquakes, wars and plagues to guide humanity because some clarity in their delicate perceptions was worth preserving, despite the rending chaos which could easily have torn their words in shreds and scattered them to the winds.

Particularly, I felt a connection to that writer who is one of the most astute calculators of chaos in human affairs, il gran’ signor Machiavelli. Many a time I stood at my window in those two months, blind, like Mr. Kurtz, to what I was looking at as I meditated on the horror of our time and the fears I have for my little niece’s future, and I felt like the divine, diabolical Niccolò avidly surveying the carnage of Florence as it continually changed hands.

He, I knew, would have loved to have been alive in this moment of global upheaval and naked power grabs.

This is not a situation I would wish on my niece. But just as I feel privileged to have lived through such a crisis myself, I also think it’s a good thing for her to have experienced a world-historical event like a global pandemic so early in her life, and I hope the words I am going to give to her shortly will equally stand as an experiential guide for her going forward, something that will help to orient her as this event has done.

I am now at the design and layout stage, so the book will shortly be available for sale in the Dean Kyte Bookstore. If you would like to register your interest in purchasing a copy when it becomes available, you can do so by dropping me a line via the Contact form, and I’ll be sure to get in touch with you as soon as it is ready for release.

Tag: The Melbourne Flâneur

Two visions of Melbourne

Achtung! The track above is best heard through headphones.

It’s been a while since I have uploaded to The Melbourne Flâneur what I call an ‘amplified flânograph’, an analogue photograph taken in the course of my flâneries around Melbourne with a third dimension added to it—a suitably atmospheric prose poem read by yours truly.

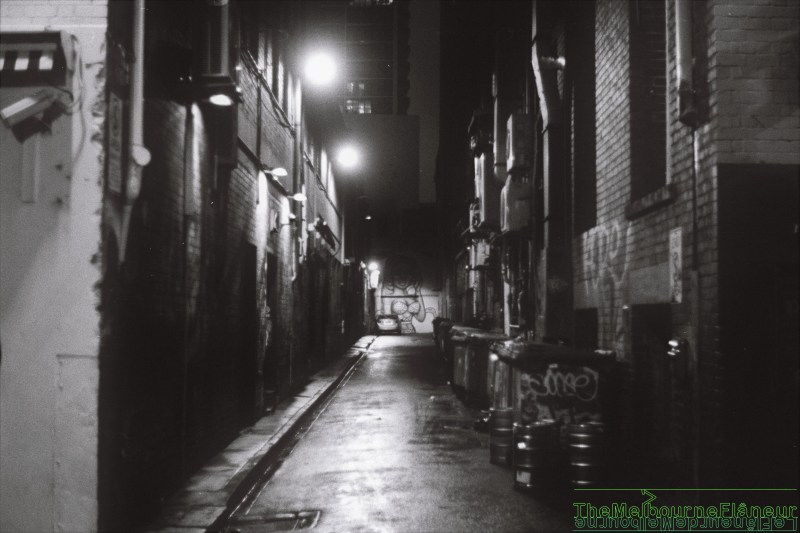

I think you will agree that voice and soundscape add a dimension of depth to this image of Uniacke court, a laneway off Little Bourke street between Spencer and King streets famous to aficiónados of Melbourne street art.

It’s one of Melbourne’s ‘where to see’ places—and no more so than when it’s raining.

The image above was not my first attempt to capture Uniacke court on black-and-white film at a very specific time under particular weather conditions.

This shot, taken on a rainy Sunday evening at 6:00 p.m. during winter last year, was the second-to-last exposure on my roll of Kodak T-MAX. It was something of a miracle, because not only did I want to capture this image on that day, at that time, under those conditions, but the laneway acts as service entrance for a number of bars and restaurants, so you have to judge the timing of the shot very well: Uniacke court tends to fill up with cars around 6:00 p.m., blocking the wonderful mural by Melbourne street artist Deb on the back wall.

I had attempted to nab the same shot less than two weeks earlier. Knowing that I had only six shots left on the roll, and that it was unlikely that I would get my dream day, dream time, dream weather conditions, and a conspicuous absence of heaps heaped up in the court, I had come past on a Thursday evening, around 5:40.

Wrong day, wrong time, no rain, and plenty of jalopies jungling up the laneway all equalled a wasted shot I squeezed off reluctantly.

But when my dream day, time and weather conditions rolled around ten nights later, you can bet your bippy I hustled my bustle up Spencer street P.D.Q. against a curtain of driving rain to clip the redheaded cutie holding court over Uniacke court.

And only one car to mar my Hayworthian honey’s scaly embonpoint!

The short ficción I’ve added in the audio track accompanying the photograph is the feeling of that image, the feeling of ineffable mystery which initially drew me to Uniacke court and caused me to make a mental note that some fragrant essence of the place makes itself manifest on rainy Sunday evenings at 6:00 p.m., and that I ought to make the effort to haul out my ancient Pentax K1000 at precisely that time, under precisely those weather conditions, and try and capture that ethereal, ectoplasmic essence on black-and-white emulsion.

Like those weird ellipses in David Lynch’s films, I’ll leave it to you to imagine what dark aura I found emanating from the fatal femme’s breast.

In a recent post, I called flânography ‘the poetry of photography’, and described it as an attempt to photograph the absent, the invisible, the unspeakable energy of places. In many ways, the addition of an expressly poetic description of the laneway and the construction of an ambient soundscape intended to immerse you in my experience is the attempt to ‘amplify’ that absent, invisible, ‘indicible’ dimension of poetry I hear with my eyes in Uniacke court.

Last week I ran into Melbourne photographer Chris Cincotta (@melbourneiloveyou on Instagram) as he was swanning around Swanston street. In the course of bumping gums about my passion for Super 8, Chris said that, while he had never tried the medium, he was all for ‘the romance’ of it.

Knowing his vibrant, super-saturated æsthetic as I do, I could see, with those same inward eyes of poetry which hear the colourful auras of Uniacke court, how Chris would handle a cartridge of Kodak Vision3 50d. And that inward vision of Chris’s vision was a very different one indeed to my own.

That flash of insight got me thinking about the way that qualitatively different ways of seeing, based in differences of personality, ultimately transform external reality in a gradient that compounds, and how, moreover, two individuals like Chris and myself could have developed radically different visions of the same subject: Melbourne.

It could be argued that, if you spend as much time on the streets as Chris and I do, the urban reality of Melbourne could rapidly decline for you into drab banality. But for both of us, Melbourne is a place of continual enchantment, though I think the nature of that enchantment is qualitatively different, based in fundamental differences of personality.

The individual’s artistic vision encompasses a ‘personal æsthetic’, based in one’s personality, which dictates preferences and choices in media which compound as they are made with more conscious intent and deliberation.

Where Chris prefers the crisp clarity of digital, which imparts a kind of hyper-lucidity and sense of speedy pace to his photos, I prefer the murky graininess of film—still compositions which develop slowly.

While Chris tends to prefer working in highly saturated colour that is chromatically well-suited to highlight Melbourne’s street art, I work exclusively in black-and-white.

And while I know that Chris labours with a perfectionist’s zeal in editing his photos so that the hyper-lucid clarity and super-vibrant colours of his images faithfully represent his vision of Melbourne, I prefer to do as little editing as possible, working with the limitations and unpredictability of film to try and capture my vision of Melbourne ‘in camera’ as much as possible.

If I were to offer an analogy of the æsthetic difference created by these cumulative preferences and choices in equipment, medium, and attitude to editing, I would say that Chris’s photographs feel more like the experience of Melbourne on an acid trip, whereas my own pictures give the impression of a sleepwalker wandering the streets in a dark dream.

The city is the same, but the two visions of it, produced by these cumulative technical preferences and choices, are very different.

But where does the vital æsthetic difference come from?

Ultimately, the personal æsthetic which dictates different preferences and choices in equipment, media, and attitudes to editing are couched in two different artistic visions of the same subject, and these inward visions produce two radically different ways of physically seeing Melbourne.

With his crisp, colourful, action-packed compositions, Chris, I think, has a very playful, ludic vision of Melbourne: he sees it as an urban wonderland or playground.

And this is perfectly consonant with his gregarious, extroverted character. For those of us who are fortunate to know him, Chris is as much a beacon of light diffusing joyous colour over Melbourne as his own rainbow-coloured umbrella, and I notice that he effortlessly reflects the colourful energies of everyone he talks to.

If I am ‘the Melbourne Flâneur’, I would describe Chris Cincotta as—(to coin a Frenchism)—‘the Melbourne Dériveur’: his joyous, playful approach to exploring the urban wonderland of Melbourne with the people he shepherds on his tours seems to me to have more in common with Guy Debord’s theory of the dérive than with my own more flâneuristic approach.

Being an introvert and a lone wolf on the hunt for tales and tails, while I’m as much a ‘romantic’ as Chris, it’s perhaps little wonder that the ‘Dean Kyte æsthetic’ should be very different, more noirish as compared to Chris’s Technicolor take: the romance of Melbourne, for me, is dark, mysterious, and I see this city in black-and-white.

Melbourne is not a ‘high noir’ city like American metropolises such as New York and Los Angeles. Rather, there is a strain of old-world Gothicism in Melbourne which, when I sight sites like Uniacke court through my lens, reminds me more of the bombed-out Vienna of The Third Man (1949), or the London of Night and the City (1950).

And if Chris is a beacon of colourful light to those of us who know him, the ambiguity of black-and-white is perhaps a good metaphor for my character, from whence my personal æsthetic proceeds.

If there is a ‘Third Man’ quality to Melbourne for me, it’s perhaps because there’s a touch of Harry Lime in me—the rakish rogue. Like Lime, whose spirit animal, the kitten—an ‘innocent killer’—discovers him in the doorway, you might find me smirking and lurking in the shadows of a laneway, revelling, cat-like, in the mysterious ambience of ‘friendly menace’ in the milieu, what I call ‘the spleen of Melbourne’.

If you haven’t checked out Chris Cincotta’s work on Instagram, I invite you to make the comparison in styles. It’s fascinating to see how two artists can view the same city so differently. And being so generous with his energy, I know Chris will appreciate any comments or feedback you leave him.

The flâneur as dandy

Here’s a newsflash for those of you who have not been keeping up to date with the hourly drama that is the weather in Melbourne: it’s been a bit funny lately.

Melbourne is perhaps the only city in the world where the question, ‘What will I wear today?’ is an existential dilemma.

We’ve been having the ‘worst of both worlds’ these past couple of weeks: it’s been both muggy and cold, which means that if you dress for the humidity, you freeze, and if you dress for the rain, you sweat.

That was the uncomfortable dilemma I was living with when Melbourne photographer Tommy Backus (@writes_with_light on Instagram) caught me on the steps of the Nicholas Building in Flinders lane last week.

I first met Tommy in Frankston, where he took some handsome portraits of me, which you can check out here. It was a pleasure to run into him again, and a greater pleasure still to receive a compliment from him on my fashion. I had just come from a business meeting, and before that I had been cursing the ‘bloody Melbourne weather’: cold and rainy as it was, it was too damn muggy to be wearing a three-piece wool suit.

Such is the price of being a dandy, or ornate dresser, in Melbourne: your Melbourne Flâneur, dear readers, suffers on the crucifix of fashion.

You will doubtless recall that when I set forth my thoughts on what is a flâneur, I said that, in addition to being a pedestrian and the keenest possible observer of the æsthetic qualities latent in the urban environment, the flâneur must necessarily be a dandy.

This was the most controversial premise in my argument, but the logic was straightforward and sound: Charity, I said, begins at home, and a man who does not regard himself first and foremost as a worthy æsthetic object of investigation is highly unlikely to bring to bear that acute perspicacity to æsthetic detail in the external world which I attribute to the flâneur if he does not first of all attend to the details of his own person.

But let us not be in confusion about the dandy philosophy. As M. Baudelaire cautions us: ‘Dandyism is not, as many people who have hardly reflected on the subject appear to believe, an immoderate taste for clothes and material elegance. These things, for the perfect dandy, are merely symbols of the aristocratic superiority of his spirit.’

As Philip Mann discerned in his book The Dandy at Dusk: Taste and Melancholy in the Twentieth Century (2017), at heart, æsthetically-minded men who are accursed with the ‘pathology’ of dandyism seek to square the circle of life and art, of form and content, to unify self with the meaning that self creates. The dandy, says Mann, seeks ‘to become identical with himself’—that is, to become identical with his ideal of personality by applying the rigorous æsthetic of a work of art to his own life.

Thus, it is not difficult to see (as per Baudelaire) that the dandy’s outer person may be the canvas of his mind, and that the object of the ‘art’ of dandyism is to integrate the wood of character with the veneer, the outer being a platonic reflection of the inner.

But again, let us not fall precipitately into the error which would appear (superficially at least) to be the next logical steppingstone in our analysis of the dandy life: the dandy is not a ‘fop’.

Though he is androgynous by his very nature, arrogating to himself the feminine privilege of display, there is nothing ‘effeminate’ about the dandy.

As Beau Brummell—the first dandy, and an implacable foe of the kind of ‘peacockery’ in men’s fashion which he set himself to reform in the early nineteenth century—presciently divined, the essence of masculine beauty is of a ‘moral’ (that is, a spiritual) variety, in contradistinction to the physical quality of feminine beauty, and lies in masculine virtues, to wit:—simplicity, rectitude, honesty, discrimination, rigour and sobriety.

Along these classic lines, Brummell designed for himself the first modern ‘suit’—the perfection of masculine costume which, although it has been endlessly tinkered with, modified and refined since his day, will never be superseded by any masculine costume anywhere in the world, precisely because it gives the perfect outward form to the inner, spiritual qualities we associate with that being we call a ‘man’.

The dandy, in seeking to ‘become identical with himself’, identical with his ideal of personality, is not the epitome of masculine beauty because his clothes give him some special ‘aura’ he would otherwise lack, the way that dress, lingerie, makeup and jewellery heighten a woman’s allure and dissimulate her flaws; it is rather because he is at his ‘most transparent’—his most naked, even—when he is fully and perfectly dressed.

Any woman will tell you (by her behaviour, if not by her words) that the thing all women find most attractive in men is not their confidence, but their congruence—the transparent alignment of thoughts, words, and actions.

‘Honesty’ is a closely related quality in the constellation of masculine virtues which comprise congruence, and likewise, any woman will tell you (probably by her words, and certainly by her behaviour) that the thing she finds least attractive in a man is any whiff of ‘dishonesty’, any lack of transparent congruency in his thoughts, words and actions.

And it certainly does not go without saying that in adhering with especial scrupulousness to the rigorous and merciless rules of correct masculine attire which Mr. Brummell was the first to articulate, that a man cannot depart from the masculine virtues of simplicity, rectitude, discrimination and sobriety and still consider himself to be a dandy.

In other words, in contradistinction to what ‘many people who have hardly reflected on the subject appear to believe’, there is no place for the garish or the gaudy in the dandy’s wardrobe. Display for its own ebullient sake (that is, to ‘draw attention to oneself’) is exclusively a quality of the feminine.

The dandy does not ‘seek attention’. Rather, attention naturally finds him;—for we are always attracted to someone who shines with the aura of self-knowledge—including the knowledge of the ‘beauty’ of his own being, which he wears proudly, honestly, transparently for all the world to see, with modest confidence.

We are, in fine, attracted to anyone who gives evidence of being congruent with himself, for such a man, we know, is not easily found, and if he gives evidence of this, it is likely that he is in possession of other masculine virtues, such as honesty, reliability, dependability.

What distinguishes the dandy, however, from even the man who is very well-, very correctly, dressed with respect to ‘the details’ of his deportment, is that the dandy transcends the rules.

When anybody asks me, I tell them that if I were to define my personal style, it would be to say that I am ‘outrageously conservative’ in my approach to fashion.

That is, while I follow the rules scrupulously, as in the photograph above, some hint of my Aquarian nature always escapes the repressive, saturnine influence of Capricorn in me, whether that’s in the fine rainbow pinstripe of the otherwise sober black suit; the almost perfectly complimenting blue floral shirt and tie; or the bottle-green snapbrim Fedora, the Akubra I wore as a flâneur in Paris, with its jaunty red feather.

While perhaps outrageous in themselves, taken as an ensemble, they contribute to an effect of conservatism so extreme that they transcend sobriety in a rather unique way, one which conveys (if I am correctly interpreting the compliments I tend to get from people) the intense creativity and originality I bring to my work as a writer, which is always tempered by my equally intense adherence to precision, correctness, tradition, and ‘bonne forme’.

That is the vital æsthetic difference, the piquant je-ne-sais-quoi of exotic quality I bring to the bespoke writing, editorial and publishing concerns of my clients: like a tailor labouring in a noble and venerable tradition, they know that I will not only follow ‘the rules of good form’ scrupulously, but that, as an irrepressible artist, I will innovate to an unexpected degree within the very narrow latitude of creativity those rules allow to create a document unique to them.

What thinketh you, dear readers? Is the world ripe for a resurgence of dandyism—of ‘beautiful men’ who say and think and do in alignment with the highest versions of themselves? And do you agree that attention to the æsthetic essence of oneself is a cornerstone to being a flâneur?

I’m interested, as always, to contend, defend and generally converse with you in the comments below.

And I recommend you also check out Tommy Backus’s photographs on Instagram. As I said to him last week, it was nice to be able to put names to some of the kooky characters I’ve clocked around town.

Better viewing through chemistry

It’s a bit cheeky, but in today’s post, I’m sharing with you the same video I posted on The Melbourne Flâneur vlog last week. The same, that is, but different.

I just got back some Super 8 footage I shot in Bendigo from the folks at nano lab, Australia’s small gauge film specialists. At the time I wanted to get the video above online, the reel of Kodak Tri-X was at their lab in Daylesford undergoing ‘magic’.

So I sneakily put some ‘placeholder’ shots into the intro and outro which I hoped I would be able to later replace with some Super 8 footage—if it was any good.

Tri-X, as Kodak’s signature black-and-white film stock, is very difficult to wrangle. You can get some absolutely magical shots with Tri-X, but it doesn’t peer into the shadows very well, so you have to be either very good or very lucky—or both—to get consistently good results from it.

I’m not that good. In Bendigo, I was experimenting with the manual exposure settings on my trusty Minolta XL 401 Super 8 movie camera, so much of what was on the reel came back overexposed.

But when I dragged the gamma way down on the footage, I got some lovely shots of the Venus Pudica in Rosalind Park and the Alexandra Fountain—the more so, I think, for their being so grainy. Brief as they are, I think they add a nice bit of contrast to the digital footage in the video, and I’d love to hear your reactions.

People are always a bit nonplussed when they discover I’m so hipped on Super 8. As I was finishing up the shot of the Talking Tram trundling into Pall mall, a guy came up to me and asked me why I was shooting on film—as if I was breaking some bourgeois law of conformity.

‘Most people are using digital,’ Constable Plod of the Conformity Police complained as he signed my citation.

Shooting on Super 8 is indeed an expensive hobby, but there’s a qualitative æsthetic difference to Super 8 which sends me.

In my previous post, I stated that flânerie is an ‘altered state’: the invisible poetry which hovers behind objects in the urban environment is made visible through the flâneur’s ‘long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens,’ as M. Rimbaud puts it.

And in my recent post on flânography, I argued that this artform I had coined was the ‘poetry of photography’. I declined in that post to set forth my thoughts on the relative merits of analogue and digital photography vis-à-vis flânography, but a discussion of Super 8 seems like a good place to examine that distinction.

For me, the medium of film—and particularly Super 8—goes much further than digital photography and videography can in manifesting that ‘invisible poetry of the visible’ I talked about in the earlier posts. The chemistry of film grain does something magical that pixels cannot do in making that elemental molecular and atomic substrate vibratingly visible.

You can see that most pointedly in the overexposed shots I inserted into the video, where raking down the gamma reveals the Venus Pudica and the statues of the Alexandra Fountain as hardly anything more than dense constellations of buzzing black and grey atoms on a white field.

For me at least, the ‘murkiness’ of film is more like how I actually see and experience the world—a kind of ‘darkness at noon’.

Don’t get me wrong: I’ve got 20/20 vision the same as you. But those of you who have read Dean Kyte’s books will know that they’re a bit of a ‘trip’: even the most banal and quotidian experience erupts for yours truly (c’est moi in the snappy chapeau) in recursive dimensions of abstract meaning, and much more than digital videography, Super 8 has the ‘look’ of my life—the flâneurial experience of groping mole-like through the dazzling, sun-bright darkness of the blindingly obvious.

There’s a high-resolution quality to the experience of flânerie which the low-resolution quality of Super 8 paradoxically matches in a Baudelairean correspondance.

If you compare the video footage to the Super 8, I don’t think we will be in too much disagreement when I say that the digital footage looks more ‘like’ the things depicted in Bendigo than the film footage, the same way a realist painting of a person, tree or building looks more ‘like’ the subject than an impressionist version of same.

But when I got my Super 8 footage back from nano lab, the black-and-white flâneurial footage looked more like how I remembered Bendigo to look from the distance of a week and a few hundred kilometres. There is not that dead, flat ‘factuality’ which raw digital footage has, but a reconstitutive ‘being’ in film footage—as though it’s happening all over again, but for the first time.

As a medium, Super 8 has a look more like our memories—fuzzy, fragile, juddery and inexpertly framed. And shot on Tri-X, even cars and people look different when rendered through the rheumy eyes of Super 8: a scene as modern for me as two weeks ago now looks like it took place in a distant past.

In the altered state of flânerie, you are aware of the density of things, but also of their porous transience, and somehow the fragility of Super 8 captures the ‘eternality of the ephemeral’. You can see the grand buildings of Bendigo’s Charing Cross passing behind the Talking Tram in the footage: these magnificent buildings have lasted for over a century, but they too will eventually fall into dust.

As Céline (Julie Delpy) says to Jesse (Ethan Hawke) in Before Sunrise (1995) as they regard a poster for a Seurat exhibition: ‘I love the way the people seem to be dissolving into the background. … It’s like the environments, you know, are stronger than the people. His human figures are always so – transitory.’

I feel the same way when I look at the shots I took of the Venus Pudica: the tenacious endurance of inertia in marble sculpture—and also its fragility—are equally manifest when you see the outlines of this goddess fading in and out with the buzzing, porous granularity of changing sunlight registered so subtly and yet so roughly and approximately on Super 8 film.

Last year I asked and answered the question, ‘Are there flâneur films?’, and my conclusion was that the flâneur in film is more a quality of certain films themselves—something in the way they are shot and edited—than a human character or presence within them—prototypical flâneur movies like Before Sunrise to the contrary.

Despite the expense of shooting on film, Super 8 seems to me to be the perfect medium to produce such a ‘flâneur cinema’ or ‘cinema of flânerie’ precisely because the medium itself is attuned to this more impressionistic way of seeing the world, and because the camera itself is lightweight, discreet and versatile—ideal for a dandy engaged in curious æsthetic espionage.

As Jeff Clarke, the CEO of Kodak, has rightly observed, we—human beings—are analogue too; we’re not digital.

Our bodies and the world we live in are not made up of pixels. We’re not reducible to passels of ‘data’. It’s meet that we should see the world with the same messy, organic frame as Super 8.

And it’s the handcrafted, artisanal experience of working with film, working with something as real and tangible and fragile as myself, that really sends me when it comes to shooting on Super 8.

I feel a sense of vital involvement, my total being is engaged when I work with film. It’s the rapport of one physical, analogue being working with another. And this vital engagement of energies between real, living things is one of the qualitative æsthetic differences of working with film.

If I could have said one thing to Constable Plod which explained why I was using film instead of digital to capture the shot of the Talking Tram, it would have been that. As a ‘film maker’, I felt like I was actually ‘making’ something which required art, craft and skill to accomplish.

There’s no particular ‘skill’ required in digital photography or videography, but using film demands the development of skill—particularly the skill of patience, which is hardly required in our HD, ADD world where you can carelessly click a pic with your phone.

I had to wait twenty minutes at the corner of Pall mall and Mitchell street to ultimately get the shot of the Talking Tram passing through Charing Cross. I had my camera set up on my dinky tripod, my settings checked, double-checked, and triple-checked. I had tested the tension of the pan lever several times and the position of the spirit level. I had all my senses on high-alert for the least spectre of a tram shimmering in the furthest distance of that broilingly hot day—all so I would have enough time to get set for it when it passed into frame.

And one of the upsides of working with film is that I think my videography has benefited enormously from the development of the skills demanded by film. I’m much more deliberative in my framing and composition when I set up digital camera, and much more attentive to the qualities of light.

It’s over to you, chers lecteurs. What do you think?

Do you agree with ‘us analogue purists’ that film is far superior to digital in every æsthetic respect, or would you rush to the fray to defend ‘the way of the future’ against the infidel Luddites?

Are you interested in getting into film? Were you once into film and ‘went digital’—and would you like to go back?

I look forward to having a lively discussion with you in the comments below.

And if you would like to look at all the raw footage I shot on Super 8 in Bendigo (including some alternate takes which didn’t make the cut in the video above), I’ve posted that below. Nothing fancy, no music or sound effects, just the facts, ma’am.

Baudelaire’s dark Valentines

Today on The Melbourne Flâneur, I take a flânerie around Bendigo, pausing only in my perambulations to breathe some poetic airs upon your ears in beautiful Rosalind Park.

The good burghers of Bendigo named their green space after the heroine of As You Like It, but as you can see in the video, there is something otherworldly about this ‘emerald isle’ in the midst of the city, such that it reminds one of the enchanted island of The Tempest.

It’s the perfect locale for a little poetry-declaiming, and with the rather Parisian skyline of Bendigo’s Pall Mall mansard-bristling at my back, I read you my translation of Charles Baudelaire’s sonnet “L’Idéal”, from my book Flowers Red and Black: Love Lyrics & Other Verses by Baudelaire.

There’s always an erotic edge to my writing, and like a pendulum, I oscillate between the sublimely romantic and the frankly pornographic, so it should come as little surprise that I am such an admirer of Baudelaire, or that I have translated so many of his love poems.

Though I had some slight acquaintance with M. Baudelaire beforehand, it was as a flâneur in Paris—the city of flânerie, the city of Baudelaire—that I really got to know the divine, diabolical M’sieu.

As I perfected the art of wandering the streets of Paris, the Latinate rap of Baudelaire’s high-flown rendering of low-brow subjects was a constant cicerone in my ear, directing me towards the tawdry tableaux which Paris flashes like her undergarments at the voyaging connoisseur of voyeurship.

‘Parisian life is abundant in poetic and marvellous subjects,’ Baudelaire observed. ‘The marvellous envelopes us and suckles us like air, but we cannot see it.’

Certainly I feel the same way when I set up my camera to capture those little vignettes of Bendigo, shots of rien de tout, which bracket the video above. Statues, street art, architectural details, empty vistas:—Bendigo (which bores the Bendigoans) is fecund in that surreal quality of the marvellous, the poetry which hovers behind the banality of things much-seen.

Baudelaire’s ambition was to make the Parisian see this invisible air in which he ambulated, to turn the exquisite flâneur experience of the ephemeral into a flâneur poem. In the same way, if there is any ‘poetry’ in the shots of nothing I insist on boring you with in my videos, it is the poetry of the ‘boring’ urban life which Baudelaire, lover of novelty and ennui, both wanted to escape from and escape more fully to.

Flânerie is an ‘altered state’ which reveals the invisible poetry of the visible city. Baudelaire, as the père of flâneur philosophy, was an inveterate chasseur after artificially-induced altered states which liberated the surreal poetry that is the resident spirit of the banal.

He praised the state of drunkenness as the essence of the poetic experience, and wrote a scholarly treatise on the poetic effects produced by hashish. And of course, Baudelaire was an amateur of that other intoxicating, protean substance which produces a poetic effect on men: la femme.

As a flâneur, he was a Daygamer avant la lettre, as may be witnessed by his ode to an anonymous passer-by. It’s one of Baudelaire’s most delicate and evanescent love poems, ineffably romantic and yet unmarred by any effeminate sentimentality whatsoever.

In a handful of lines, Baudelaire perfectly conveys that ephemeral experience which all men of the city know:—the lightning-flash moment when you see a woman you desperately want to approach surge forward from out of the crowd; the single second in which you clearly see a whole parallel existence with her; and the second afterwards when, jostled on by the crowd, you decline to embrace the destiny with her which you so clearly previsioned:

A bright light… then the night! Fugitive beauty

In whose glance I have been suddenly reborn,

Will I never see you again in all eternity?Elsewhere, very far from here! too late! perhaps even never!

For I know not where you fly, and you know not where I go,

O you who I might have loved, O you who knew it!Translating Baudelaire is not easy. As Alan Ginsberg remarked, if you can’t read him in the original, you have to take the aggregate of all the translations in English to get a sense of what he is saying.

It’s not that Baudelaire’s French is particularly difficult, although he does some vexing things with tense that English is not supple enough to elegantly convey. It’s rather that the images he manages to paint by combining a lofty, distant tone with the startling incorporation of things deemed ‘unpoetic’ produces a remarkably lucid effect with remarkable compression.

As with Shakespeare, there’s quite an unusual ‘range’ in Baudelaire’s language. He’s equally at ease with the most recherché classical allusions as he is with the slangy argot of the Parisian gutter, and he demands not only a requisite range from his English translator but a sense of how to convey in modern English the quality of ‘shock’—and even of ‘offence’—produced by this admixture of tone.

Few translators who have ‘tried their hand’ at Baudelaire have a good sense of him, methinks, for with the grotesquerie of his subject matter, it is too easy to make a schlocky parody of Baudelaire in English.

One requires an exquisite sensibility for the sublime horror (or horrific sublimity) of everyday life to approach Baudelaire on his own terms of unquiet desperation with normal, bourgeois existence. In fine, one requires an ample dose of that quality which he himself defined (finding no better word for it in French) as good old-fashioned English ‘spleen’.

In Flowers Red and Black, the poem which most conveys this choking, stifling sense of sublime horror (or horrific sublimity) is “The Jewels”, my translation of “Les Bijoux”.

It’s the most sensual, erotic poem in the collection, and the one I am always asked to read at poetry gatherings because it’s almost like a short story: in the space of a few minutes, people feel as though they have been completely transported into the small, stuffy chamber, lit only by firelight, in which Baudelaire and his Creole mistress, Jeanne Duval, are engaged in foreplay.

The heady incense of the smoke, the play of weird lights rising from the fire, the music of Jeanne’s ‘chiming jewels’, and the way she undergoes a metamorphosis before the bard’s eyes, changing into a tiger, swan, slutty angel and classical catamite by turns, always gives people the hallucinatory sense, sans drugs, of the ‘altered state’ which Baudelaire experienced in sexual love.

And yet, because the banality of this everyday scene takes on a heightened potency and is attenuated to such an exquisite degree, there is a stifling, almost suffocating sense of sublimity into which an erotic horror enters, like the almost painful pleasure of the ‘petite mort’.

As romantic as his love poems are, there is nothing wilting and effeminate about Baudelaire, which is perhaps why women like this book. His voice is forceful and potent, and it seems to combine well with my own style as a writer, such that we make some ‘beautiful music’ together.

I’m thinking of publishing a second edition of Flowers Red and Black, revised and expanded, even including some of Baudelaire’s prose poems. But that project is some way in the future.

In the meantime, I have a very limited stock of the first edition on hand—about a vingtaine. It makes an original St. Valentine’s Day cadeau, and the dames do grok it. As I say in the video, I’ve been reliably informed (regrettably post facto) that ladies have regaled one another with my verses in bed.

I’ve also had a friend rip off my translation of “Les Bijoux” and try to pass it off as his own poem to placate a squeeze who wasn’t in the mood to be squeezed. (She saw through his play at once, which only served to further inspire her ire.)

You can purchase a copy through the Dean Kyte Bookstore, but if you want to buy a copy from me directly, you can do so either by clicking this link, or by registering your interest with me via the Contact form.

This allows me to get in touch with you to arrange payment and delivery details. It also enables me to get some particulars from you so that I can write a thoughtful, personalised message on your behalf to the lucky person you want to give the book to.

Plus, I will flourish the magic wand of my Montblanc Noblesse over the flyleaf and affix my personal seal in wax to it, so your first edition will be doubly exclusive.

Flânography: Photography as poetry

One of the icons that Melbourne is known for is “The Skipping Girl”, Australia’s first animated neon sign, which formerly advertised the Skipping Girl Vinegar brand.

From the Art Deco rooftop of a converted factory in Victoria street, Abbotsford, she jumps rope over 16,000 times per night, and one of the most romantic things to do in Melbourne at night is to take the route 12 or 109 trams to Victoria Gardens and watch this 84-year-old icon repeat her nightly performance.

An icon is an image, a symbol which substitutes for an absent other whose spirit is supposed to reside in the icon, animating it, and receiving the adoration which would otherwise go directly to the sacred personage, if they were present.

It’s interesting, therefore, to reflect that the Skipping Girl, who was once the icon associated with a brand of vinegar which is no longer manufactured, has become the genius loci of Melbourne. But when I took the ‘flânograph’ above with my vintage Pentax K1000, she did not represent for me so much a symbol of ‘old Melbourne’ which had disappeared, but someone who had disappeared, an absent other I will always associate with the Skipping Girl.

As I explain in the video below, the first time I encountered the Skipping Girl, I was stepping off the 109 tram with a Dutch girl I had picked up eight hours earlier. We were about to go upstairs to her apartment, across the road in Richmond, and make love.

When I saw that neon icon beating time against the night, it was like seeing an X on a treasure map: this icon of Melbourne would always be, for me, a perpetual monument to a personal conquest, marking the spot of my greatest victory in Daygame.

In his essay “The Poetic Experience of Townscape and Landscape” (1982), documentary filmmaker Patrick Keiller describes the flâneur as a literary motif signifying two types of experience. Following Schiller’s distinction between the naïve and sentimental poet, I think we can summarize Keiller’s two types of flâneur as likewise being ‘naïve’ and ‘sentimental’.

The ‘naïve flâneur’ is more like the classical, nineteenth-century dandy conceived by Baudelaire. As Keiller says, he ‘takes the city as his salon’. He’s a romantic adventurer—a Daygamer, in essence—whose ‘chance encounters are largely with people’ rather than with those architectural citizens of a city, buildings and monuments. Whatever dreamlike quality there is in the encounter between this flâneur and the city derives from ‘his surrender to the randomness of urban life.’

The ‘sentimental flâneur’, en revanche, is a solitary dériveur who drifts through the city as though it were a petrified dream, experiencing the ‘long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens’ which renders the banal street marvellous. As Keiller says, this flâneur ‘may meet others, he may fall passionately in love, but this is not his motive, it merely enhances his experience by enabling it to be shared.’

As a Melbourne flâneur, I have always felt like a synthesis of these two figures, but tending more towards the latter. I can ‘do’ Daygame, I can take adventitious advantage of the randomness of urban life to seize a romantic encounter; but, being a genuine introvert, I am more constitutionally inclined towards solitary drifting through the externalized ‘Forms’ of my thought which streets, parks, statues, monuments and buildings seem to symbolize for me.

Keiller cites Surrealist poet Louis Aragon, who, in Le paysan de Paris (1926), describes this paradoxical sensation of seeming to experience the platonic forms of things embodied in the constitutive elements of the city.

‘The way I saw it,’ Aragon writes, ‘an object became transfigured: it took on neither the allegorical aspect nor the character of the symbol, it did not so much manifest an idea as constitute that very idea. Thus it extended deeply into the world’s mass…’

For Aragon, this sensation was a presentiment of ‘a feeling for nature’, but it would be more specific to say that it was a feeling for the ambiguity of urban nature.

‘I acquired the habit of constantly referring the whole matter to the judgement of a kind of frisson which guaranteed the soundness of this tricky operation,’ Aragon writes.

This ‘frisson’, as Keiller observes, is not dissimilar from that feeling of ‘rightness’ a photographer intuitively senses immediately before he presses the shutter release button. This sensation is the moment when a swatch of street cuts itself out of the banal tableau of urban nature and quadrates itself in the abstract frame of a mental viewfinder as an ‘image’, as something marvellously photogenic.

The sentimental flâneur, Keiller contends, carries a camera to record these marvellous transfigurations. But, sentimental soul that I am, when I went back to photograph the Skipping Girl, nearly a year after my conquest of the Dutch girl, I was not photographing the Skipping Girl and her miraculous transformation of the night.

I was attempting to photograph the absence of the Dutch girl, for whom she was an icon.

In his book with Jean Mohr, Another Way of Telling: A Possible Theory of Photography (1982), John Berger writes that ‘[b]etween the moment recorded and the present moment of looking at the photograph, there is an abyss.’ It is an abyss of absence, of ambiguity, which carries with it ‘a shock of discontinuity’.

‘The ambiguity of a photograph does not reside within the instant of the event photographed,’ Berger writes. ‘The ambiguity arises out of that discontinuity which gives rise to … [t]he abyss between the moment recorded and the moment of looking.’

In my ‘flânograph’ of the Skipping Girl, that abyss was doubled:—for there would be an abyss between the moment of looking at the developed photograph and the moment I was now recording, just as there was, for me, an abyss between the moment I was recording and the moment the photograph was intended to record, some ten months earlier.

As a writer, I have long played with the idle idea (impossible to realize) of writing a book completely without words. The flânograph of the Skipping Girl was one of a series of photographs I took with my battered Pentax for a ‘picture book’ I intended to compose for my little niece, a wordless collection of black and white images of things and places I had encountered in my flâneries, and which, in their silent ambiguity, might give a child an ineffable, inenarrable sense of the life of an uncle she had never met.

Was there an enduring, impalpable resonance of the unseen, unknown and unknowable event sensible, apprehensible by the viewer of the photograph of the Skipping Girl, démeublé of its ostensible subject, the Dutch girl? Could the feeling—menacing; enigmatic; melancholy—of this particular square of urban nature—what we might call ‘the Spleen of Melbourne’—‘speak for itself’, eloquently and without words?

These were the questions I wanted answers to. And like Eugène Atget, of whom Walter Benjamin said that he photographed the empty streets of Paris as though they were ‘scenes of crime’, I went back and photographed the scenes of my Melburnian conquests—the Skipping Girl, a sodden Windsor place, a certain tree in the Carlton Gardens—now eerily empty of myself and the lovers of a moment who had left mortal wounds in my heart.

This feeling for the menacing, enigmatic, melancholy ambiguity of urban nature which precedes the click of the shutter; this ineffable, inenarrable frisson is what I call ‘flânography’, and it’s something other than photography—something more than merely ‘writing with light’.

It’s a sensitivity to the absent, the invisible, the unspeakable. It’s the poetic cry of the silent image which establishes historical evidence of the ‘baffling crime’ which is the personal ‘situation of our time’, and which the asphalt jungle gives colour and cover to.

If there is a ‘noirishness’ in the flânograph of the Skipping Girl, it is because, when I look back on my brief encounter with the Dutch girl over that abyss of ambiguity which it records, I feel (as I do after all my amours) like the victim of a ‘baffling crime’ at the hands of a femme fatale.

Like a consummate con artist who gets his pocket picked, I gamed her and ended up getting gamed by her.

When writing with light starts to become ‘poetic’ instead of merely prosaic; when the weak intentionality that a photographer possesses to express himself through a box is leveraged to the maximum, such that the urban landscape is transfigured and transformed into an image that is personally expressionistic, then photography starts to become ‘flânography’.

If you are a photographer and would like to explore how I can provide you with bespoke assistance in sensitively curating your work into an artisanal-quality book through provision of my Artisanal Desktop Publishing service, I invite you to download this brochure, or to contact me directly.

Are there flâneur films?

Vitus Bacchausen wishes that somebody would make a movie about the flâneur, but admits, for prescient reasons, that such a film would be impossible to make within the constraints of commercial cinema.

Why, Bacchausen wonders, have there been no ‘flâneur movies’?

There are two answers to this question. Firstly, one may adduce a not insubstantial list of characters in film who might be described as flâneurs.

The first, and most obvious, candidate is Scottie Ferguson in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), who, when quizzed, gives his profession as ‘wandering’. But you can also reel off putative examples like the wandering protagonists of Antonioni’s films, such as Lidia in La Notte (1961), Vittoria in L’Eclisse (1962), and the photographer of Blowup (1966).

You could point to Jesse and Céline in Before Sunrise (1995), or the eponymous heroine of Amélie (2001). Petra Nolan of the University of Melbourne even makes a plausible case, in her PhD thesis, for Walter Neff, the vagabond insurance salesman of Double Indemnity (1944), as ‘the cinematic flâneur’ par excellence.

The key word is ‘plausible’.

All the examples adduced above are plausible, and a convincing prima facie case could be made for any of them as cinematic flâneurs, one which would appear to refute Bacchausen’s contention that the figure of the flâneur has not really found his place in cinema.

But my second answer to Bacchausen’s question refutes the one I’ve just given.

I would say that if you look more carefully at any of the films cited above, you must come to the conclusion that they feature characters who partake in flânerie, but that these characters are not themselves flâneurs pur-sang.

In an earlier post, I gave a fairly strict definition of what is a flâneur. I offered three traits which I regard as non-negotiable characteristics in any definition.

Firstly, the flâneur is a pedestrian. He walks, not occasionally, but as his primary and preferred mode of transport.

Secondly, he is an acute observer of the world that files past him as he walks, and as Bacchausen notices, there is, in the sport of observation, a distinctly æsthetic end to the chase. The flâneur is a hunter who chases after beauty.

Thirdly, there is a pronounced element of the dandy in the character of the flâneur. Charity begins at home: unless he firstly recognizes himself to be a worthy æsthetic object of attention, it is highly unlikely that a man who is not assiduously attentive to the details of his own deportment is going to exhibit the level of unusual acuity of attention toward the æsthetic details of the external world which I ascribe to the flâneur.

A man may walk shabbily abroad looking longingly after beauty, but that man is not a flâneur. He is the Average Frustrated Chump you see shambling down Swanston street.

Given the definition above, it’s hard to see how the characters adduced in the first answer are flâneurs, though it can certainly be conceded that they partake in the activity of flânerie in a more or less dilettantish way.

Jep Gambardella, the Roman giornalista of La grande bellezza (2013), is the only character in film I can think of who satisfies my three-point definition as a ‘cinematic flâneur pur-sang’.

So the question remains: Are there flâneur films?

The answer is yes, but it is the character of the films themselves, rather than any characters they contain, which may be regarded as ‘flâneuristic’.

At the Toronto International Film Festival in 2016, Slavoj Žižek made some intriguing remarks vis-à-vis. Hitchcock; to wit—how Hitchcock’s films have an uncanny quality, at certain moments, of appearing to ‘think for themselves’.

In Psycho (1960), for instance, there are two extraordinary moments, one immediately after the shower scene and the other immediately before the second murder. In both cases, the camera detaches itself from the point of view of the character it has locked onto and acts ‘queerly’, as though it had an intelligence and agency of its own, moving through space and looking at things quite pointedly, as though it were mutely trying to tell us something, the way our unconscious appeals to us through images.

Žižek calls this ‘thinking through film’, and it’s a highly rarefied cognitive process which seems to emerge from the apparatus of cinema itself—something like Baudelaire’s sensation that the image of sky and sea, and a little yacht trembling on the horizon, seemed to be thinking through him—‘musicalement et pittoresquement, sans arguties, sans syllogismes, sans déductions’ (‘musically and pictorially, without quibbles, without syllogisms, without deductions’).

Meditating on Žižek’s remarks, I began to ask myself what a cinema of flânerie might look like.

In fact, flâneur films are the oldest kind. They have their roots in the actualité, the single, locked-off shot, without pan or cut, of the miracle which a moment of everyday life becomes when you train a camera at it for so long that it transcends its boring banality—like the shot of a sunset unfolding behind the Melbourne CBD which I’ve included at the head of today’s post.

The camera’s ability to gaze fixedly at a detached detail is like, and yet unlike, the flâneur’s acuity of observation, for our eyes do not ‘frame’ things. When a shot is composed and unblinkingly held for minutes on end, and when, as in the video above, it is implied that this perspective is closely aligned but not identical with the point of view of an observer we cannot see, there is the uncanny sense that the camera itself has ‘intelligence’.

A film becomes ‘flâneurial’ when a moment of documentary actuality enters into it and is sustained well beyond what the average viewer would regard as a reasonable length of time.

To my mind, Ozu is the master of this kind of flâneurial cinema. His ‘pillow shots’ are moments of ventilation in a film where architectural features and irrelevant details are held for longer than they would ordinarily be. Ozu’s stubborn refusal to pan or dolly, to allow his camera to ‘look away’, imbues it with a sense of wilful, alien intelligence.

The other attribute of flâneurial cinema is the offshoot of the actualité, the ‘phantom ride’. This is when the camera is placed on a train, tram or car, and, without moving itself, appears to float or glide like a ghost, registering the succession of actual events which pass it by.

The classic phantom ride, the masterpiece of the form, is the famous “A Trip Down Market Street” (1906). Strapped to the front of a cable car, the camera floats towards the Ferry Building for 13 minutes, registering the life of the street with that alien fixity of attention we see in Ozu, never turning its ‘head’ to gaze about itself as a real flâneur would.

The capacity of the camera to move in this gliding, floating fashion, simulating human ambulation but very different from it, is a quality that Antonioni makes good use of in his passeggiate.

In La Notte, the camera, raised at some elevation behind Lidia, appears almost to stalk her as it stealthily tracks her tacking between bollards. In Blowup, in the key scenes set in Maryon Park, the camera is subtly detached from the point of view of the photographer. It pans to sweep the scene in a movement more eerie than a human head-turn because of its mechanical smoothness. Or, in a moment of startling volition, it gazes up at the branches of a tree in what we realize only afterwards was its own ‘point of view shot’.

This uncanny sense of the film possessing its own intelligence and agency, principally through the camera, but also through cutting and the rest of the constitutive apparatus which compose a film, is, I think, what Žižek means when he talks about ‘thinking through film’.

‘To understand the film,’ he says, ‘you should include into its content the message delivered by the autonomy of form. It’s at that level that true thinking in cinema happens.’

When a film has the volition to move—or not move—through the world as it wishes, and to study with its own fixity of attention those details of actuality which arrest it in its passage, the character of the film itself becomes ‘flâneurial’.

What do you think?

Are there characters in movies you would actually define as flâneurs, or, like Bachhausen and myself, are you at a loss to think of any who really meet the measure?

Is it possible for films to ‘think for themselves’, as I’m suggesting?

I’m interested to hear your comments below.

Relieving the burden of academic writing

One punishing summer day in January, I ‘flânographed’ this Atlas in my anklings about town as a Melbourne flâneur. One of a pair of Telamons who formerly held up the portal of the Colonial Bank of Australia, he now graces the doorway of an underground bicycle garage at the University of Melbourne.

An appropriate place for him to struggle with his eternal burden, perhaps.

As I said in this post, I most often describe the art of writing as being ‘sculptural’ or ‘architectural’, and often a writer feels like this fellow, trying to balance an elaborate structure of thought on the top of his head.

For an academic writer such as the Masters student or PhD candidate, the sense of ‘oppression’, of being weighed down by the burden of this elaborate architecture of thought you are trying to build in words can give you the haunted, worried expression this Atlas wears.

Many students arrive at the Masters—or even the PhD—level lacking confidence in their ability to write essays, reports and theses to an academic standard. And the sense of anxiety is doubled if your first language isn’t English.

In 2005, Wendy Larcombe, Anthony McCosker, and Kieran O’Loughlin conducted a study at the University of Melbourne. They wanted to know whether providing a ‘thesis-writing circle’ to doctoral students from both native English-speaking and non-native English-speaking backgrounds had any effect on the students’ confidence and abilities as academic writers.

Larcombe, McCosker, and O’Loughlin published the results of their study in the Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice in 2007, and if you’re a postgrad struggling with the burden of preparing a research thesis, their article makes for encouraging reading.

Two problems typically confront postgrads: the development of their skills as academic writers, and the development of their confidence.

As Larcombe, McCosker, and O’Loughlin found, both doctoral candidates and their supervisors generally perceive the academic skills support services provided by universities to be ‘too generic’.

As a student at the postgraduate level, you require editorial support that is specific to your discipline. The writing advice and strategies offered by your editor must be bespoke to your needs, framed within the intellectual context and discourse of your discipline, and relevant to the concept you are trying to express in your thesis.

But students arrive at the postgraduate level with different editing skills and editing needs.

Editing the writing of students is something that supervisors don’t always feel is their ‘rôle’. When they do correct spelling mistakes or faulty syntax in draft chapters without providing explanation or instruction, students can feel ‘demoralized’ by the implicit negative judgment of their work, according to Larcombe, McCosker, and O’Loughlin.

A crucial part of developing your skills as an academic writer involves developing your confidence. Having a ‘writing facilitator’ who is independent of your supervisor, one who provides editorial advice tailored to your discipline and to your specific sticking points as a writer, improves both your ability and your confidence.

Larcombe, McCosker, and O’Loughlin found that being able to discuss what you are working on with another writer who offers supportive, positive feedback grows your confidence as an academic writer. Being tutored in the craft of writing by a professional who is able to intelligently discuss your thesis with you helps you to develop the practical skills of writing in a way which is relevant and specific to your discipline.

With my Bespoke Document Tailoring service, I offer postgraduate students in Melbourne a bespoke and personal approach to copyediting and proofreading their theses.

As a professional writer, my specialty is the logical architecture of written language, the organization of ideas at their deepest level so as to ensure maximal comprehension by your readers.

As an Associate Member of the Institute of Professional Editors (IPEd), I’m bound by a Code of Ethics, so I can’t help you to cheat, but as a writing facilitator, I can provide independent editorial support which is specific to your discipline and which complements the structural advice you’re receiving from your doctoral supervisor.

If you’re interested in working with a professional writer who can help you to find your own unique style on the page, tutoring you in the development of your voice, I invite you to contact me, or to download a free brochure describing how I can help you with your Bespoke Document Tailoring needs.

What is a flâneur?

A question I am often asked is, ‘What is a flâneur?’ As I explain in today’s video, a flâneur is a kind of ‘Parisian idler’.

Flâner (the French verbal infinitive from which the noun is derived) means both to stroll, saunter, walk or wander more or less aimlessly, and to loaf, laze, or lounge about. The ambulatory motion of the former would seem to preclude the stasis of the latter:—how does one walk and sit at the same time?

This paradox is merely the foundation of a complex structure of irreconcilable logical paradoxes which comprise the ludic enterprise of flânerie and constitute the characteristics of the flâneur.

The question then follows, what is it like to be a Melbourne flâneur? If to be a flâneur is to be a Parisian idler, then to be a Parisian idler in Melbourne would seem to add one paradox de trop to the complex character of the flâneur.

Pas du tout.

I find a lot of similarities between Melbourne and Paris. People often ask if Melbourne is like Europe. The answer is yes. Of all the Australian capitals, Melbourne has the strongest ties to Europe, and despite its fraternal links to Greece and Italy, there seems to me to be an unmistakable soupçon parisien to its arcades and laneways, its bars and cafés, such that I sometimes think of Melbourne as being ‘Paris-on-the-Yarra’.

Key to Melbourne’s Parisian flavour is its walkability. It is, like Paris, a remarkably ‘walkable’ city: you can go very far on foot, and to be a flâneur you must be prepared to travel Melbourne without a car.

Fortunately, its famous tram network (the most extensive in the world) serves roughly an analogous rôle to the Paris Métro, being thoroughly integrated into the peculiar character of the city and the fabric of its streets.

This means that if you get tired of walking in Melbourne, you don’t have to go too far to find the nearest tram stop!

The reason why the flâneur is necessarily a pedestrian is because the pace of idle observation is measured by the foot. In his essay Le peintre de la vie moderne (1863), Charles Baudelaire defines the flâneur as a ‘passionate observer’ whose home lies in the crowd; as a ‘mirror’ large as the crowd itself; as ‘a kaleidoscope endowed with consciousness’ which reflects its movements.

In fine, the flâneur is an instrument of observation which reflects the colourful spectacles it observes in two ways: both matter-of-factly, as a mirror reflects actuality, and interpretatively, as a thoughtful subject who reflects upon what he sees.

You can see why the observational avocation of the flâneur might be an amusing exercise for someone whose vocation it is to be a writer: the writer’s desire to transcribe the external details of reality with the rigorous exactitude of a piece of recording equipment finds its playful analogue in his detectival attempts to divine the hidden causes and motivations behind the riddle of events observed obliquely, en passant.

The art of writing is essentially the art of thinking, and there must necessarily be objects upon which the writer may reflect if he is to express his thoughts articulately. To wander dreamily through a beautiful city like Paris or Melbourne is, for a writer, both physical and mental exercise: it allows him scope to play with objects in the landscape, practising his powers of observation and description as he reflects them and reflects upon them in articulations he makes to himself.

‘To feel and to think’, to satisfy the desires associated with such abstract work, to cultivate the ideal of masculine beauty about their persons, this, for Baudelaire, is the sole profession of the dandy, whom he conflates with the flâneur, that ‘prince who revels in his incognito everywhere he goes.’

Indeed, there must always be something of the dandy about the flâneur. Among his many paradoxes, this slumming spy who loves ‘to be in the midst of the crowd and yet hidden from it’ is very much a ‘man of fashion’ in the classic sense, like an heir-apparent travelling in a foreign country under an assumed name, with nothing but the unmistakable marks of his elegance to betray his royal birth.

You cannot be a flâneur pur-sang and not have more than a soupçon of the dandy about you. Precision of observation does not extend to external objects before it takes account of the correctness of one’s own comportment.

It is perhaps surprising to notice how many great writers, whose idle profession of feeling and thinking takes place in the ‘backstage’ of life, away from the observation of others, such that these spies are rarely the cynosure of all eyes, have nevertheless a touch of the dandy about them, a concern for dapper deportment.

An orderly mind is best expressed by orderly dress. And it is rare to find a writer who expresses himself on the page with unusual stylistic panache and who does not also possess some exquisite sprezzatura in his personal style.

Elegant writing, like elegant suiting, is the mastery of convention and the transcendence of strict limitations which define the correctness of expression.

With my Bespoke Document Tailoring service, I can help you to write elegant business documentation which is bespoke to your needs. If you want your documentation to reflect a bespoke image, to possess that æsthetic difference, the piquant je-ne-sais-quoi of exotic quality, why not collaborate with a writer who brings the keen perception and care for detail of the flâneur to your concerns?

I invite you to contact me to arrange a measure. And if you enjoyed this article, or if it aroused ideas of your own you would like to share with me, I would love to hear your thoughts on the flâneur in the comments below.

Write like a sculptor

A few months ago in Brisbane, I shared an extract with you from the book I am writing. This week on The Melbourne Flâneur, I flâne around Docklands, taking advantage of the warmer weather to sit by the Yarra and read you a new extract.

At this stage, I am approximately 60 per cent of the way through the second draft of the book—which is where the ‘real writing’ occurs. I don’t write so much as rewrite.