A few months ago in Brisbane, I shared an extract with you from the book I am writing. This week on The Melbourne Flâneur, I flâne around Docklands, taking advantage of the warmer weather to sit by the Yarra and read you a new extract.

At this stage, I am approximately 60 per cent of the way through the second draft of the book—which is where the ‘real writing’ occurs. I don’t write so much as rewrite.

I use a lot of metaphors to describe my approach to writing. Sometimes I think of it as ‘architectural’, other times as ‘musical’, or even ‘painterly’. But oftentimes when I think about my process of writing and publishing a book, I compare it to ‘sculpting’.

As demonstrated in the video above, ultimately I am writing thought. The action of the scene is simple enough: walking downhill at night. The thoughts that take place on that flânerie, however, are not simple to describe or make intelligible to the reader.

Michelangelo (some of whose sonnets I have translated), said that ‘every block of stone has a statue inside itself’, and that ‘to free the captive / Is all the hand which obeys the intellect may do.’

It is as though I am ‘hewing’ my thoughts out of a block of dense fog in my mind, and it takes several passes with the chisel and the file over successive drafts to sculpt those thoughts into their final, perfect form in words.

If you work from a plan or outline for your book (and you always should), this is like a sculptor’s maquette: it is a skeletal, bare bones structure which represents all the parts of your book and their relations to each other.

Writing your first draft is like modelling in clay: it’s a time to get your hands dirty and play. I always write the first draft by hand because it allows me to explore the lineaments of my thought, probing and shaping its first vague outlines.

The second draft, as I said, is where the ‘real writing’ takes place. It is the longest and most difficult part of the process because you have to ‘carve out’ what is vague and implicit in the first draft.

The second draft is about maximal amplification and clarification, so I rewrite my entire book, carving out every detail that I passed over lightly and summarily in the first draft until I’m satisfied that my thought is fully explicated.

In the extract I share with you in the video above, this is the point you find me at with regards to that walk downhill: all the implicit thoughts in back of that simple action are now explicit.

It’s perfectly acceptable to ‘overwrite’ in your second draft: as Michelangelo said, sculpture is the art of subtraction, of ‘taking away’—but you can’t take away words you haven’t written to begin with.

The third draft is about subtracting the inessential, and if you are writing a book for the first time, this is the point where you may consider engaging a professional editor to help you decide what to take away.

All editors have different methodologies, but as you might imagine, with my Artisanal Desktop Publishing service, I tend to regard your words as though they formed an object in space, something I can see ‘in the round’, like a sculpture, and I’m very good at discerning what is inessential and what is core to the structure of your book.

If you enjoy this video and would to see more ‘episodes’ in the future, as I update you on the progress of my next book, taking you inside my Artisanal Desktop Publishing process, I’d appreciate it if you like the video on Vimeo or leave an encouraging comment. You can also share your own steps to writing a book with me in the comments below.

Category: Dean Kyte products

A ‘Slow’ approach to offering value

I want to thank all my friends who have accepted the invitation to follow my adventures on The Melbourne Flâneur vlog. As I commence my enterprise, offering a bespoke, artisanal approach to document preparation, it means a lot to me to have your support.

It’s also an honour and responsibility to produce online content for an audience who has committed to watch it.

In thinking about how to produce online content that is meaningful, engaging and valuable without bombarding or overwhelming you, I was influenced by Jasmine B. Ulmer’s article, “Writing Slow Ontology” (2017).

In the spirit of the ‘Slow’ movement (as in Slow Food, Slow Cities, etc.), I want to propose a ‘Slow’ approach to producing online content, one that does not bombard you with volume or overwhelm you with fast pace, one that is, as Ulmer says, ‘not unproductive’ but ‘differently productive’.

As opposed to the consumptive and disposable model of online content production that predominates, I won’t spam your inbox with clickbait. You won’t hear from me often, but I hope that when you do receive notification of a new post, you will look forward to the content I offer.

To my mind, online video should open a space in which to breathe for the viewer, not fill a hole hungry to consume. In line with the bespoke, artisanal value promise of my enterprise, I want whatever leaves my hand to be the best that I can make it.

I called my vlog The Melbourne Flâneur because I wanted to bring a more ‘pedestrian’ pace to producing online content, introducing Paul Schrader’s notion of the transcendental style in film to online video.

In the video above, you’ll notice my love of ‘leveraging boredom’—holding on shots of ‘nothing’ at the beginning and end, moments of ‘ventilation’ which encourage you to pause, breathe and observe with me in my flânerie.

The fast-paced, high-volume approach to content generation is opposed to the bespoke æsthetic of the handcrafted, artisanal products and services I promote. To write and publish even a slender volume like Brazen Gifts for Gold took more than a year of my life.

Writing is a true ‘manual labour’, but, as Ulmer observes, it is also a labour of time and being in which we don’t just ‘do’ writing but ‘live’ writing. To be a writer is to live an artisanal lifestyle.

Value emerges from this condition of artisanship: all the being and ‘life/time’ of the writer is imbued in the bespoke, handcrafted book, not merely in the words he sweats over to make perfect, but in the total ‘livery’ of his libello.

Likewise, in the video content I offer you on this vlog, in which places are allowed to be and breathe, I hope you enjoy a vicarious oasis of valuable respite from the overwhelming pace of our amped-up existence.

How does a ‘Slow’ approach to creating online content resonate with you? Do you agree that we could benefit from a more thoughtful, deliberative pace to online video production? I’m interested to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

Network with a Melbourne author

As an emerging writer, you gain valuable experience by networking with other writers. Their fresh ways of seeing the world open exciting new directions for your own writing.

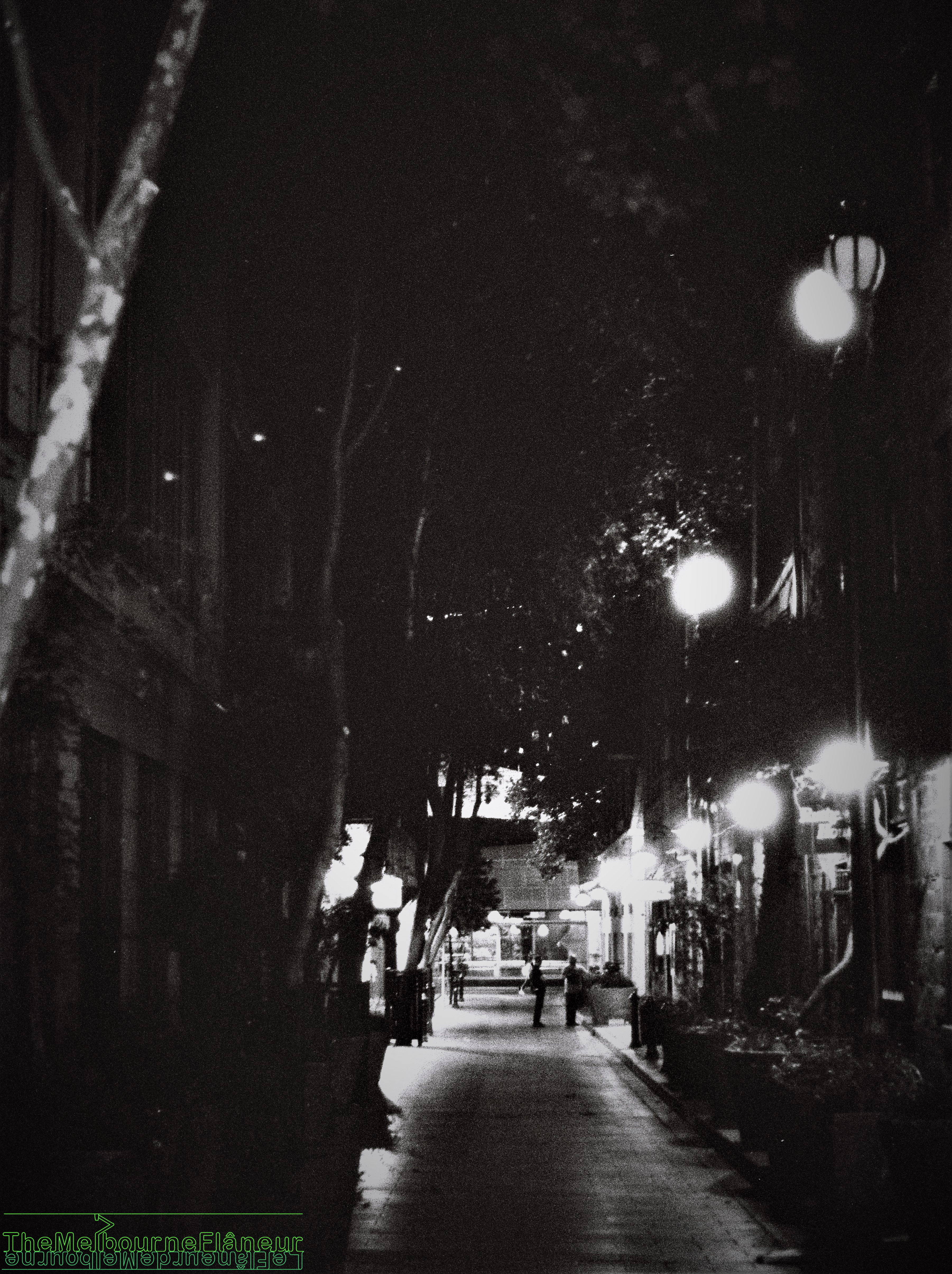

As he demonstrates in this prose poem based on the ‘flânograph’ above, Dean Kyte doesn’t just see the world differently, he hears it differently too. And the poetic way in which he describes his personal experiences is idiosyncratic to say the least.

For the Melbourne Flâneur, even moments of banality, loitering in Melbourne at night, waiting for the perfect shot, are freighted with epiphanic mystery…

If you want to take your writing to a new level of mastery, it pays to network with an editor rich in literary experience, one who shares your passion for le seul mot juste because he happens to be a fellow Melbourne author.

And if you’re a writer in French seeking to make yourself perfectly compris dans la langue de Shakespeare, Dean Kyte can provide editorial assistance bespoke to your needs with his Bespoke Document Tailoring service.

Enjoy the augmented experience of this ‘amplified flânograph’. To connect with Dean and experience his bespoke approach to your editing needs, drop him a line via the Contact form.

Melbourne’s Parisian underbelly

Melbourne transforms itself into a foreign wonderland at night. Armed with my Pentax K1000, I venture forth after-hours to capture ‘a Brassaï moment’—the moment when Highlander lane, between Flinders street and Flinders lane, reminds me of the square Caulaincourt in Paris—the setting of my first book, Orpheid: L’Arrivée (2012).

As a writer, I move from obscurity to clarity. For me, writing is a flânerie through the chiaroscuro of consciousness and unconsciousness. I enjoy the frisson of venturing into dark places which are foreign to me—like alighting from a taxi in a cosmopolitan European locale late at night, not sure where you are, barely speaking the language, some menacing silhouettes in the milieu to greet you.

Before I was ever a Melbourne Flâneur, I was a flâneur in Paris, the Mecca of flânerie. In L’Arrivée I wrote about my experience of feeling both fearful and fearless, arriving alone, late at night, in a small Parisian square in Montmartre. Despite barely speaking the language, I had a strange sprezzatura, a strange confidence in myself—in my mission and message as an artist—going forward.

Do you speak the language of the land? If you are a writer in French, Italian or Spanish, can you make the obscurity of your message clear to readers in English, combining the formal and the vernacular with the bravura of the native-speaker?

With my Bespoke Document Tailoring service, I can help you translate the complexity of your experience into words which allow you to feel heard and understood by your readers.

To explore how I can help you communicate your message with a bespoke approach which complements your literary voice in your native tongue perfectly, go to my Contact form to arrange a discreet and private measure with me.

How to paint a picture with words

Persuading a client or investor to share your vision is like seducing a woman: you have to paint a clear picture by using vivid and evocative language which appeals to the emotions of your reader.

In this video, Dean Kyte demonstrates how to paint a vivid picture with words as he reads an extract from his latest work in progress. Still in Brisbane, the Melbourne Flâneur paints an impressionistic snapshot of his thoughts and feelings before Rupert Bunny’s Bathers (1906) in the Queensland Art Gallery, making the painting come vividly to life.

As Dean demonstrates, by tailoring the language of your message precisely to your intended reader, you can make even a restricted format like a text message as vivid and evocative as haïku, striking your reader with an emotional impact which allows her to enter into your experience and share your vision in a way which provokes her to enthusiastically respond.

To find out how Dean can help you distil your message to the same point of vivid clarity with his Bespoke Document Tailoring service, fill out the Contact form to arrange a discreet and private measure with him.

An excerpt from “Things we do for Love”

On location at South Bank in Brisbane, Dean reads an excerpt from his book Things we do for Love (2015), available in the Dean Kyte Bookstore.

An audio version of the story is available for purchase on Dean’s Bandcamp page. You can also purchase the eBook/audiobook combo in the Bookstore for the price of the eBook alone.

If you’re in Brisbane right now and would like to book a private measure with me to explore how I can help you to publish your own book through my Artisanal Desktop Publishing service, please send me a message via the Contact form.

In a lonely street

A short story in which I speculate on the fate of a character I wrote about as a much younger man—and who continues to haunt me still.

Enigma of the afternoon

In this prose poem, Dean Kyte meditates on one of Melbourne’s most alluring paradoxes…

You can purchase the audio track on Bandcamp by clicking the link below:

Cinescritos preview

A sneak preview of my forthcoming Blu-ray Disc Cinescritos: Writings in Image & Sound, which will be released in early 2019 in the Dean Kyte Bookstore. The disc comes with a full-colour, illustrated essay booklet.

Advance orders are welcome. Please use the Contact form to get in touch with me.

You can also watch the trailer below: