Brisbane, David Malouf exclaims exasperatedly in Johnno, is a city that ‘would have defeated even Baudelaire!’ ‘People suffered here without significance,’ he writes. Where hell is Sartre’s bourgeois autre, Brisbane is too middling, too mediocre even to be a suburb de l’Enfer, ‘[a] place,’ in Malouf’s avis, ‘where poetry could never occur.’

For Johnno, for Malouf, – for his Brisbanian Dante without even the dignity of Ravenna to suffer in, – it’s a city whose very soul is soullessness, characterized by the ramshackle, makeshift nature of the place. Exiled from the empire of Western Europe, no classicism could possibly take root in this muddy colony of the maddog English.

And yet all my spleen with la vie de l’ennui en Australie was born in the ideal of this sultry river city, swampy Venise of vaporous, féerific CityCats plying gauche rives of odiferous mangroves. And all mes désirs de Paris were born of mes flâneries to the Dendy, the Valley, to Indooroopilly or Rosalie in search of movies and thumbedthrough bouquins de seconde main.

City of ferries like Venice, city of bridges like Paris, like our national epic, the story of Brisbane is yet to be chanted. The civic classic sinking its piliers et poutres into Brisbane’s shores will sing l’esprit of contingency, of ersatz imperfection, and even of mouldy ugliness, of baudelairean putrefaction!

— Dean Kyte, “O Brisbane! O Baudelaire!”

Welcome back, chers lecteurs, to another year of investigating the æsthetic philosophy of flânerie here on The Melbourne Flâneur.

The Christmas/New Year period found Your Humble Servant sweltering in higher latitudes than the name of this vlog implies as I returned to my home city of Brisbane for the first time in over five years.

I spent seven weeks in the River City over December and January, and after what was probably the longest period of absence from it in my forty-year intimacy with Briz Vegas, when I stepped out of the chantier that has been dug from the defunct Roma Street Station, I felt like I was finally seeing the city in which my first flâneurial balbutiements were babyishly burbled and trébuchements were trippingly taken in its true, very reduced dimensions.

Sensation curieuse!

Even when Brisbane was the hellish destination that lay at the other end of a homeward journey that began at the gare du Nord, not even then did I feel, with all my desolate weeping at the sight of our Venetian-style City Hall—the most beautiful in Australia—that Brisbane is a very strait and provincial place.

It is not that my experience of the world has grown that very much larger in five years of absence from Brisbane, but that I became thrillingly aware that, in an exile from Paris I expect to be a permanent removal from the most vivifying spectacle I have ever beheld, ‘down under’, in the infernal antipodes of culture and civilization, what might be called ‘the lessons of Paris’ have at last been absorbed into my vision of the local scene during the last sixteen years of my literary life.

In fine, it is my eyes—the scope of my vision and the cognitive lens of the French language that I apply over everything—that has grown that much larger in the absence when Melbourne, as the local analogue for la vie parisienne, has been the concrete structure mediating the theoretical construct of applied flânerie on Australian soil, and has primarily occupied my vision, both physical and mental.

It is not a slight to Brisbane to say that I found the first city of my experience ‘smaller’, less abounding in absorbing, diverting novelty than in the days when I used to live on the Gold Coast and some of my first expeditions in flânerie involved weekends in Brisbane searching for the altered states of experience that movies, books and art—the ‘culture’ I was in thirst of—represented for me.

I still have affection for it. But I’ve travelled so far in my thinking now from those days in my twenties when, like the ‘hero’ (?) of David Malouf’s great Brisbane novel Johnno (1975), I was so desperate for a better life than South East Queensland could offer, that I just had to chuck the whole place up for a jaunt to the Mecca of flânerie itself.

Among the kilo or so of books I decided to bring with me on my expedition back to Brisbane was Johnno. I wanted to read it again ‘in situ’, to have the actual locations Malouf describes—and which are so familiar to me, despite the very different Brisbane of his day—before my enwidened eyes.

For it’s the case that the Brisbane of Malouf’s wartime childhood and post-war youth was just hanging on in my own, in the Bjelke-Petersen eighties and Wayne Goss nineties. Even then, it was ‘so sleepy, so slatternly, so sprawlingly unlovely!’

Johnno is so sensual a book that you might say that Malouf manages to poetically capture and convey something impalpable yet inhering about Brisbane—its ‘aroma’, perhaps—the way a fragrance lingers—for an ‘old Queenslander’ like myself—in an old Queenslander like the one in which I was staying in Aspley, throwing me back into childhood memories of my great-aunt’s home in Red Hill.

That’s perhaps not a surprise because this short novel, which has become a ‘classic’ of Australian literature, was published less than a decade before my birth. The city of the sixties Malouf describes in the later pages is definitely the ‘beautiful one day, perfect the next’ Bjelke-Petersen bog of glass, steel, bitumen and bad paving I remember from my enfance in the eighties and nineties.

It was the same all over. The sprawling weatherboard city we had grown up in was being torn down at last to make way for something grander and more solid. Old pubs like the Treasury, with their wooden verandahs hung with ferns, were unrecognisable now behind glazed brick facades. Whole blocks in the inner city had been excavated to make carparks, and there would eventually be open concrete squares filled with potted palms, where people could sit about in Brisbane’s blazing sun. Even Victoria Bridge was doomed. There were plans for a new bridge fifty yards upstream, and the old blue-grey metal structure was closed to heavy traffic, publicly unsafe. There would eventually be freeways along both banks of the river that would remove forever the sweetish stench of the mangroves that festered there, putting their roots down in the mud….

It is a sobering thing, at just thirty, to have outlived the landmarks of your youth. And to have them go, not in some violent cataclysm, an act of God, or under the fury of bombardment, but in the quiet way of our generation: by council ordinance and by-law; through shady land deals; in the name or order, and progress, and in contempt (or is it small-town embarrassment?) of all that is untidy and shabbily individual. Brisbane was on the way to becoming a minor metropolis. In ten years it would look impressively like everywhere else. The thought must have depressed Johnno even more than it did me. There wasn’t enough of the old Brisbane for him to hate even, let alone destroy.

— David Malouf, Johnno (1998, pp. 206-8)

I have a friend who reminds me of Johnno, but I ought to be careful what I say, for I’m sure that return fire could be made and that several of my friends probably think that I am Johnno—the discontented dilettante spewing spleen about the cultural desert de l’Australie, constitutionally incapable of getting on with life or along with people.

‘Johnno’ is Edward Athol Johnson, but for my readers abroad, he’s Harry Haller or Holden Caulfield; he’s the type of stifled rebel who doesn’t march to the beat of a different drum because he cannot even get in step with himself.

All that differentiates Johnno from those more famous examples is that he’s an Aussie—given to larrikin pranks with a long fuse, and feeling, from the distance of the infernal antipodes, the unreachability of the ‘culture’ he associates with Europe even more profoundly than an American might do.

An utterly characteristic gesture is that, when he departs Brisbane for darkest Africa to have his Heart of Darkness experience in the Congo, at his last meeting with the novel’s sensible, cissy narrator, it is Johnno who gives Dante the going-away present of a volume of Rimbaud.

He fancies himself a voyant whose vision is narrowed, unfairly hobbled by the unspeakable blahness of Brisbane, but even when he gets to Paris, improbably impersonating a Scottish English teacher since the French won’t entrust their sous to someone with an Aussie accent, Johnno finds himself trapped in the same ennui as in Brizzy.

Johnno’s whole life is the abject and undigested lesson that I learnt on my first unhappy day in Paris:—the realization that you port your troubles as a fardeau with you; that putting a fresh landscape before your eyes doesn’t fundamentally change you or your destiny; and that if you are miserable in Brisbane gazing at the Skyneedle, you will be just as miserable in Paris looking balefully at Notre-Dame.

… [U]nless the police were making one of their periodical raids (which they did every time there was a bomb blast or a murder under the trains at Châtelet, [the rue Monsieur-le-Prince] was as quiet and suburban as the Parc Monceau.

I got used to the raids. Like everyone else I would tumble out of bed at the first sound of the armoured car swinging in over the cobbles, and by the time the first hammering came on the door downstairs would be out on the landing with my passport, while Johnno shouted from the landing below: ‘Twice in a week, this is! It’s driving me crazy. You can see now why I wanted to get out.’ But when the uniformed officers arrived with their tommy-guns at the ready he was desperately eager not to give trouble. His student permit had expired several months ago, and if they had wanted to the police might have arrested him on the spot. But they were after terrorists, not petty violators of the civil code. They returned Johnno his papers with yet another warning, turned over the bedclothes while one of them covered him with a tommy-gun and the other went through the motions of a quick frisking, and it was over. Then my turn. And the others further up. Generally after a ‘visitation’ Johnno’s nerves were too shaken to go back to bed, and after three or four minutes of futile argument I would agree to go out with him and walk until dawn. We would stroll along the silver-grey quays where the tramps slept, stop and have coffee at one of the all-night bars, play the pinball machines whose terrible crash and rattle, in those early hours, had a more violent effect on my nerves than any flic with his toylike tommy-gun.

— Malouf (1998, pp. 166-7)

That’s the other thing about Johnno. Although he wants to put a bomb under Brisbane and claims to hate Paris, he’s a coward without the Rimbaudian convictions of the true æsthetic terrorist—which is what the dandy-flâneur essentially is in his explosively, kaleidoscopically light-filled heart of darkness.

Where Johnno boasts to Dante, in Brisbane, of consorting with a spy and assassin who ‘look[s] and act[s] like a bank clerk’, he hasn’t that true saboteurial spirit that Flaubert counselled—that one should be bourgeois in one’s habits so as to be radical in one’s art.

Johnno hasn’t any art, apart from the lie and the prank. His poetry and performance art is acting out a fantasy of rebellion against the very staid existence that he is just as pathologically adjusted to as Dante.

Both have what might be called a ‘free-floating discontent’ that manifests itself in a way that is superficially divergent but is actually, in terms of the deep structure of the novel, regrettably convergent.

It’s one of the weaknesses of Malouf’s book—which comes out in the overdetermined yet dribblingly vague and unresolved third act—that it’s ultimately not clear what moral he intends for us to draw from the mémoire of unlikely comradeship between this odd couple, who do not really contrast with one another, nor undergo any complementary inversion of rôles.

Rather, I think Malouf fumbles intuitively and yet artlessly into some clumsy irresolution about the character of Australian life, its vacancy, its makeshift nature, which is particularly potent in the psychogeographic character of Brisbane itself.

It’s hard to put one’s verbal finger quite on it, but there’s a certain abortive character to Australian life, a kind of unconscious will to failure or a dread of success that manifests in the irresolute half-lives of vacancy that both Johnno and Dante are more or less resigned to—and which mars even the best books of our literature, as it mars this one.

Perhaps more than any city on this continent, Brisbane sunnily manifests this blankness of temperate sameness which inspires Malouf/Dante to say that it is a city so deprived of the light and shade of spleen and the ideal—the blanc et noir possibilities of flânerie—that ‘[i]t would have defeated even Baudelaire!’

I don’t dispute this; I utterly repudiate it.

The whole intellectual history of my life disproves Malouf’s contention: As bitter and sinister an orchid as Baudelaire can spring up in these climes to stalk its streets and milk it of its healing poison.

Johnno may kick senselessly against the pricks of Brisbane and Dante may resist them with quiet desperation, but neither of these characters have that largeness of vision, that structural scope I indicated at the beginning of this article, to see Brisbane in its just proportions and its proper place in the broader context of modernity.

The vision and experience of Paris can fundamentally impress itself upon neither of these characters—eminently Australian in their unformed, ersatz natures—and it cannot fundamentally remold and refine them for the ironic æsthetic appreciation of the local scene en Australie because neither Johnno nor Dante, despite their hungry reading, have even a tentative hypothesis for an æsthetic lifestyle such as the one I formed in my splenetic traipsings through Brisbane and took with me to Paris, intending to prove or disprove my æsthetic theory there.

In fine, neither of these characters are really flâneurs—and yet Johnno is a flâneurial novel, and not just because Johnno and Dante spend most of the book ambling through its pages.

I liked the city in the early morning. The streets would be wet where one of the big, slow, cleaning-machines had been through. In the alleyways between shops florists would be setting out pails of fresh-cut flowers, dahlias and sweet william, or unpacking boxes of gladioli. After Johnno’s sullen rage I felt light and free. It was so fresh, so sparkling, the early morning air before the traffic started up; and the sun when it appeared was immediately warm enough to make you sweat. Between the tall city office blocks Queen Street was empty, its tramlines aglow. Despite Johnno’s assertion that Brisbane was absolutely the ugliest place in the world, I had the feeling as I walked across deserted intersections, past empty parks with their tropical trees all spiked and sharp-edged in the early sunlight, that it might even be beautiful. But that, no doubt, was light-headedness from lack of sleep or a trick of the dawn.

‘What a place!’ Johnno would snarl, exasperated by the dust and packed heat of an afternoon when even the glossy black mynah birds, picking about between the roots of the Moreton Bay figs, were too dispirited to dart out of the way of his boot. ‘This must be the bloody arsehole of the universe!’

— Malouf (1998, pp. 116-7)

Johnno is, for one thing, a great novel of place, which is why I wanted to read it again ‘in situ’ when I was up in Brisbane last month.

What Walker Percy, in his equally flâneurial novel The Moviegoer (1961), called ‘certification’—the ‘making real’ for a reader of a place he already intimately knows—is one of the deepest pleasures of regional literature.

Malouf paints with a looser brush than I generally prefer. It’s one that he handles adroitly when it comes to Brisbane and sloppily when it comes to Paris, which he limns in a curiously dull palette by comparison, and not, I think, by deliberate design, since the whole novel falls very badly away into busy incoherence when the action relocates to the Continent.

But the first two-thirds set in Brisbane are sketched with a colourful impressionism that is, as I said above, ‘aromatic’ of the city’s vibe even today, and Malouf treats a place that both Dante and Johnno regard as irrecuperably ugly as though it had the poetic dignity of Paris.

He certifies the city with les détails justes—with the names of streets and suburbs, with the presence of pubs that are still trading and where yours truly has sat and written, and even set some of his own scenes, drawn from his flâneurial vie in Briz Vegas, in their beery bosoms.

As a flâneur pur sang, the proper names of places, of streets and suburbs, of correct geography that allow for certification, carry an incantatory quality for me, and I sense that, for anyone unfamiliar with Brisbane, Malouf’s petites touches of impressionistic precision would enable a similar kind of ‘certification by proxy’.

Arran Avenue, Hamilton, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, the World. That is the address that appears in my schoolbooks. But what does it mean? Where do I really stand?

The house at Arran Avenue is the grim, three-storeyed brick house my father built for us in one of the best suburbs in Brisbane. Arran Avenue is a narrow dead-end street that runs straight into the hillside, with houses piled steeply one above the other on either side and bush beginning where the bitumen peters out into a track. The traffic of Kingsford Smith Drive is less than fifty yards away but cannot be heard. The river, visible from the terrace outside my parents’ bedroom, widens here to a broad stream, low mudflats on one bank, with a colony of pelicans, and on the other steep hills covered with native pine, across which the switchback streets climb between gullies of morning glory and high creeper-covered walls.

— Malouf (1998, pp. 68-9)

The afternoon before I was due to book out of Brizzy, I took a flânerie, first by ferry, then by foot, to see this mythical Arran Avenue in Hamilton, wondering if I could find a house that geographically matched Malouf’s description.

He’s right about everything: Kingsford Smith Drive, which is six lanes of roaring non-stop traffic from Pinkenba to Albion Park, is almost silent as you pass up Crescent Road alongside the high-built old Queenslander on the bluff overlooking the river.

Arran Avenue is in sight of it, a mere 75 metres away. Dante/Malouf’s street is an arcing one-block spur off Crescent Road that shortly ends in the cul de sac of some richard’s driveway.

I didn’t think I would have much luck finding a three-storey, river-facing, brick-veneer house that must be at least seventy years old, but the déco frontage of no. 19—presently up for sale, if you’re interested—fits the bill of Malouf’s description.

You might still see the river from the third-storey balcony over the shoulder of the house facing no. 19 if you stand on tip-toes.

That is certification, and there is an example of flâneurial writing right there for you, chers lecteurs: If you can draw an accurate bead on an actual location from the author’s description of it, you’re dealing with something in the flâneurial line.

In one of the most significant of its dimensions, flânerie, I have discovered in my rootless, restless wandering of a country I have only grudgingly learned to love, but which I would still blow up tomorrow with all Johnno’s anarchistic antipathy towards it, is a form of embodied poetry.

As I have amply demonstrated in flâneurial films and videos like the one at the head of this post, flânerie is the application of the lens of a poetic vision over prosaic actuality: the flâneur makes the spleen of his prosy existence in Brisbane bearable by finding, through John Grierson’s ‘creative treatment’ of the documentary matériel of his life, the poetry in his banal actuality.

It’s this that Malouf manages to partially do in his novel—viscerally, with respect to Brisbane—and which both of his characters fail utterly to do. Their oppressive apprehension of ennui in Brisbane leads to spleen, but the manifold novelty of Paris does not necessarily lead either Johnno or Dante to find the Baudelairean ideal ‘du nouveau!’ there.

La vie parisienne est féconde en sujets poétiques et merveilleux. Le merveilleux nous enveloppe et nous abreuve comme l’atmosphère ; mais nous ne le voyons pas.

Parisian life is abundant in marvellous and poetic subjects. The marvellous surrounds us and suckles us like the air, but we do not see it.

— Charles Baudelaire, “Le Salon de 1846”, Curiosités esthétiques (1868, p. 198 [my translation])

Likewise, in the sultry, fuggish atmosphere of Brisbane, the milk and honey of poetry may yet be found by a soul that is not ersatz and barely sculpted, as if modelled in wet clay, but rigorously limned and scored, the æsthetic architecture of his life—the code by which he is determined to truly live—vigorously worked out.

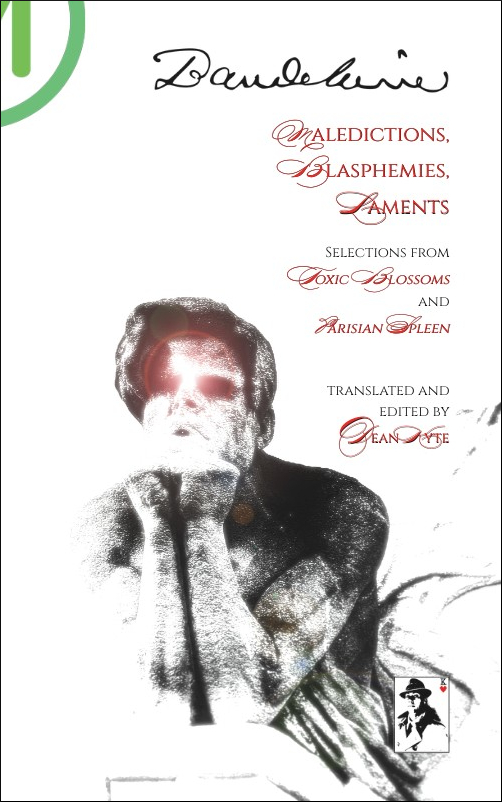

Readers, I commence a new year on The Melbourne Flâneur with an important annonce: This year I begin rolling out The Melbourne Edition of my collected works, starting with a new volume of translations of the poetry and prose poetry of Charles Baudelaire which I intend to serve as the complement and counterpoint to my own work in The Spleen of Melbourne project.

This new book, whose layout and design I finalized last month in Brisbane, is scheduled for release at the end of June. It features one-fifth of the total number of poems featured in the three editions of Les Fleurs du mal which Baudelaire (and then his mother) saw through the press, and one-quarter of the prose poems from Le Spleen de Paris.

At the time of writing, I have translated 89 per cent of the poetic and prose-poetic content I intend to include as a representative selection of Baudelaire’s æsthetic philosophy of flânerie.

And as a bonus that bridges his poetic and prosaic œuvres, I have decided to do a brand new translation of the only work of fiction that Charles Baudelaire is known to have written, “La Fanfarlo”. As one of the last tasks remaining before I bring this book to print, I will commence drafting that translation this month.

With a substantial critical monograph on Baudelaire and full-colour illustrations, Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments is going to be a very handsome volume in both its hard- and softcover formats and a valuable introduction to the work of the first philosopher of flânerie.

To register your interest in purchasing one of the first copies in June, I invite you to avail yourself of the contact form below and join the mailing list as I send out monthly updates to my readers.

Another way you can support my work and keep abreast of developments is by purchasing the audio track of “O Brisbane! O Baudelaire!” featured in this post via my artist profile on Bandcamp.

Using the link below, for $A2.00, you can become a fan of your Melbourne Flâneur on BC and stay in the loop as I drop new tracks and merch.

i enjoyed ‘johnno’…and part of it was simply brisbane….so little we have of our own…..to see and feel brisbane in the pages of a novel was a slightly uncanny experience…..andrew macgahan’s ‘praise’ similarly, though i believe praise is a better novel….(edmonstone st i think is another of malouf’s set in bris)

and for putting one’s finger on that quintessentially australian psyche…i found dh lawrences’ ‘kangaroo’ very insightful….

perhaps it is the laissez-faire attitude….perhaps it is a cultural inferiority complex,,,perhaps an unconscious fear of the vast interior of this land,,,and its dark secrets….i think it is all these and more….

but as far as the inferiority complex,,,,that is done now….as an australian ‘intellectual’ i find myself doffing no cap to the traditional western centres of excellence which have all become pale imitations of themselves…

perhaps the great charm of australians – their ability to not take things too seriously, especially themselves, is also their achilles heel….

to be sure this insouciance is part of why i love australia compared with stuffy old england…but i sense that it must also be balanced by something else,,,lest it lead to a sort of atrophy of the sensitive soul

the lucky country ain’t so lucky no more and i think this is because we never took seriously enough what we have here, which is almost anomalous to the rest of the world (or was). the tyranny of distance protected this land for a good while,,but that is long gone now…we simply did not have a clear enough idea of ourselves yet,,,of being something different to england, to europe, to america, something that was still ‘in the works’ but whose promise was already keenly felt….and now we are finding ourselves losing touch every year with the still nascent soul of this new/old land

but as long as someone keeps the great ideas alive,,,as dostoevsky said through zosimov in karamazov,,,that is the charge of those sensitive souls in every age,,,,to keep the great idea alive….the great dream of mankind freed from the shackles of ignorance…fulfilling the promise made to the pharisees and scribes 2000 years ago by Jesus Christ right before he was scourged and crucified (which indeed sealed the deal)…

man will sit at the right hand of God,,,,and that ironically enough will be the day religion dies….for it will be, as the situationists used to say as regards art, its simultaneous realisation and negation ….art become life, religion become implicit….a matter of the soul and its destiny….

love reading your insightful and precise words dean,,,,, and your devotion to your flaneurial mistress x

LikeLike

Thanks, Gav. Yes, Michael and I actually found ourselves saying that to one another on Monday—specifically invoking Lawrence: It’s typically been foreigners to these fatal shores—Mark Twain, Anthony Trollope, Nicholas Roeg on the cinematic side—who have been more insightful about what Australia ‘is’ than Australians themselves.

Thanks as always for your additions, my friend. I look forward to seeing you in person soon.

LikeLike