The title of Charles Baudelaire’s only completed book of poetry has remained an inscrutable rebus for English translators, despite the simplicity of the title’s formulation—two nouns, one concrete, one abstract, the definite article in its plural form, and a preposition implying possession of the concrete noun by the abstract.

This simple phrase, ‘Les Fleurs du mal’, presents no obvious difficulty to translation, and yet it has confounded generations of English translators for over a century, almost all of whom have collapsed in defeat on the prosaically literal, unpoetic phrase ‘The Flowers of Evil’.

In his indispensable commentary Baudelaire’s Tragic Hero: A Study of the Architecture of Les Fleurs du Mal (1961), D. J. Mossop states that a literal rendering of the central metaphor of the title might be ‘Poems (i.e. works of æsthetic beauty) written on the subject of evil’.

But Mossop is only stating half the problem.

We see at once from Mossop’s account what the basic problem for the English translator has been—the fact that the concrete noun ‘fleurs’ (literally, prosaically, ‘flowers’) is doing double service as an abstract noun in this context—but not that the second term of the equation, the abstract noun ‘mal’—traditionally interpreted by the English-speaking peoples in an absolute moralistic sense as ‘evil’—is also doing double service in its meaning.

Baudelaire’s original intention was that his collection should be published with an allegorical frontispiece, and his friend and publisher, Auguste Poulet-Malassis, gave the commission to the engraver Félix Bracquemond, who executed a number of designs based on Baudelaire’s specifications, including the variation above.

The image was to show an allegorical figure that was both skeleton and tree, rooted to the earth, and surrounded by the Seven Deadly Sins in the form of seven weedy flowers.

None of the variations that Bracquemond produced satisfied Baudelaire, and the closest that a graphic artist would come to realizing the allegorical device that Baudelaire envisioned would be in 1866, when the poet’s idée fixe was revived by Félicien Rops and applied as frontispiece over his last, brief collection of ‘scraps’ and banned works, Les Épaves.

In addition to the emblematic intent behind the formulation ‘Les Fleurs du mal’, Baudelaire’s chosen title must be understood in light of the prefatory dedication of the collection that he makes to his ‘master and friend’, Théophile Gautier.

In her 1994 biography of Baudelaire, Joanna Richardson shows that the precise wording of the dedicatory device was carefully worked out and ratified by Gautier in collaboration with Baudelaire.

On 9 March [1857], he [Baudelaire] sent the patient Malassis ‘the new dedication, discussed, agreed and authorised by the magician, who explained to me very clearly that a dedication should not be a profession of faith – which also had the fault of drawing attention to the dangerous side of the work.’

— Joanna Richardson, Baudelaire (1994, p. 210)

As elliptical and ambiguous as the title itself, the dedication to Gautier has been the source of over a century of contention as critics have wrangled over its wording, some seeing in it Baudelaire’s propensity for base flattery towards a well-placed confrère, others his talent for the most cynical satire, laughing up his sleeve at a man of letters, powerful in his day, now diminished in history’s eyes as compared to the lowly poet supplicating Gautier for his critical protection of the work.

But in lieu of the unsatisfactorily realized allegorical image that Baudelaire intended to serve as frontispiece to the collection and explain the meaning of its title, this emblematic invocation of the ‘poète impeccable’ Gautier, whom Baudelaire calls the ‘parfait magicien ès lettres françaises — perfect magician in the field of French letters’ (my translation), is the key for the English translator to properly interpret the meaning of the elusive and enigmatic phrase ‘Les Fleurs du mal’.

Théophile Gautier, Baudelaire’s senior by a decade, had been his co-researcher in the poetic effects produced by drugs when they had both been living in the hôtel Pimodan on the île Saint-Louis in the 1840s.

In “Une collaboration Gautier-Gérard: L’Étude sur Henri Heine signée de Nerval” (1955) Jean Richer revealed that, during those years, Gautier wrote a substantial part of Gérard de Nerval’s critical study on the poetry of Heinrich Heine, in which the Baudelairean notion of ‘correspondences’ found its entry into French literature from the German Romantics.

Nous préférons vous offrir un simple bouquet de fleurs de fantaisie, aux parfums pénétrants, aux couleurs éclatantes.

We prefer to offer you a simple bouquet of fantastical flowers, with penetrating scents and flamboyant colours.

— Gérard de Nerval, “Les Poésies de Henri Heine”, Revue des Deux Mondes, Nouvelle série, XXIII (1848, p. 224 [my translation])

In that short statement we already perceive the essential traits distinguishing the poems that Baudelaire will begin to lay before the public over the next decade.

The metaphorical notion of the poem as being a ‘flower’, a proportionate, symmetrical form with its regular lines of syllables branching from a single axial stem of text, an exquisite, exotic miniature that emits an æsthetically pleasing quality to the ear, one that is sonically correspondent to the pleasing scent and colour which strike nose and eye, was thus well-established in the Parisian literary milieu by the time Baudelaire embarked upon Les Fleurs du mal.

Across the Channel, we can trace an etymological line between the Middle English ‘poesy’ (imported from the French ‘poésie’) and ‘posy’, a small bunch of flowers, a nosegay or ‘bouquet’, to use Nerval’s term for the collection of works he selects to translate from Heine.

And it should be noted, in passing, that the Greek origins of their common cognate ‘poiesis’ emphasizes the ‘artificial’ nature of the poem: it is a ‘creation’, a ‘production’—a work of art, in fine, that rivals the natural beauty of God’s creation.

The archaic meaning of ‘posy’ dating from the Middle English period of Norman influence is both ‘poetry’ and an ‘arrangement of flowers’. It is also, in this obsolete usage, ‘an emblem or emblematic device’—just like the allegorical image conceived by Baudelaire as a frontispiece for his collection and the dedicatory device he worked out in collaboration with Gautier.

There should therefore be no reason why generations of English translators, with hardly an exception, should all have collapsed in defeat upon the gauche and unpoetically literal phrase ‘The Flowers of Evil’ to translate the invocatory formula ‘Les Fleurs du mal’.

Once the ancient relationship between the concrete and abstract senses of ‘poesy’ are seen, half the battle in understanding Baudelaire’s cryptic intention with this phrase is won, and the possibilities for new, more accurate essays on the esoteric meaning of the formula increase substantially.

However, the wearisome literal-mindedness of the English-speaking peoples in seeing only ‘flowers’ in ‘fleurs’ is as nothing compared to their unsubtle Protestantism, which insists on seeing nothing but absolute evil in the second term of the equation, ‘mal’.

Given Mossop’s explanation, that Baudelaire’s poems are ‘works of æsthetic beauty’ that correspond with the floral products of divine craftsmanship, the Gordian way that all comers have attempted to square the impossible circle in their minds, blasphemously affirming that concrete examples of God’s handiwork can only be, in the condensed way Baudelaire expresses himself in this phrase, Satanic masterpieces, appears to me not only the consequence of the absurd materiality of the English language, but of our gross, wrongheaded Protestantism as English-speaking peoples.

Baudelaire, to be sure, is the most absolute moralist in poetry since Dante.

But, as Mossop puts it, ‘One’s attitude may be no less moral when one is conscious of the evil that is within one, than when one is conscious of one’s own virtue and the evil of others. One may be none the less against evil, for being aware that part of one is for evil…. Similarly, Baudelaire’s complex attitude … is not the simple attitude of being “against evil”, nor is it the equally simple attitude of being “for evil”: it is the complex attitude of being “against evil including the evil part of himself which is for evil”.’

The simplistic theology of a Luther or Calvin cannot hope to cope with the Catholic subtlety of such an involuted moral argument.

Baudelaire very clearly bore the physical stigmata of a fall from moral grace.

If he did not contract syphilis from his first sexual encounter with a prostitute at the age of eighteen, within a few such encounters, he was certainly carrying within himself the seeds of a slow-acting poison that would eventually cripple him, degrade his mental faculties, and render the most peerless singer of the French language in the last 200 years almost mute.

Thus, for Baudelaire, the condition of ‘badness’, of ‘wrongness’ signified by the word ‘mal’ is not so much moral as physical:—it is from his embodied experience of ‘doing ill’—‘the evil part of himself which is for evil’—that the ‘malady’ du mal proceeds, not from the absolute, abstract condition of Capital-E ‘Evil’ that almost all previous English translators have simplistically settled upon.

As the wording of the emblematic device dedicated to Gautier reveals, when Baudelaire calls the poems gathered in his collection ‘ces fleurs maladives’, he is not referring, in the first instance, to the absolute moral principle that encompasses all that is ‘bad’ and ‘wrong’, from sin to error.

Baudelaire’s first concern is with physical health.

The titles of both of his major collections of prosody refer explicitly to the physical state of ill-health as the correspondent analogue for mental health, and the psychosomatic caduceus, the involuted double helix of the mind-body problem, the homeostatic regulation of the temporal, outer man by the eternal, inner person and vice versa, lies at the centre of Baudelaire’s conception du mal.

Hence, Baudelaire dedicates to the perfect magician Gautier ‘ces fleurs maladives’—‘these unhealthy, sickly, unwholesome flowers’—but also these ‘evil poems’, these perverse creations, these artificial ‘paper flowers’ whose ‘badness’ or ‘wrongness’ is inextricable from their formal beauty as poetry.

These are ‘fantastical blooms of imagination’—flamboyant, pungent effusions, as per Nerval—that are themselves ‘sickly’, and which induce sickness—malady—in the reader.

In 1857, the very year in which Baudelaire first published the bouquet of ‘unwholesome flowers’ he presented to Gautier, the pre-Freudian psychiatrist Bénédict Morel published his pioneering Traité des dégénérescences physiques, intellectuelles, morales de l’espèce humaine et des causes qui produisent ces variétés maladives.

In that work, Morel proposed a simple definition of human degeneration, one that would be frequently cited throughout the second half of the nineteenth century.

… [L]’idée plus claire que nous puissions nous former de la dégénérescence de l’espèce humaine, est de nous représenter comme une déviation maladive d’un type primitive.

… [T]he clearest notion we can possibly form of the phenomenon of degeneration in the human species is to represent it to ourselves as an unwholesome deviation from a primal type.

— Bénédict Morel, Traité des dégénérescences physiques, intellectuelles, morales de l’espèce humaine et des causes qui produisent ces variétés maladives (1857, p. 5 [my translation])

According to Max Nordau, who would adopt Morel’s definition, it is this derivation from a basic, healthy type of man that produces the ‘stigmata’—that is a technical, not moralistic term, Nordau assures us—of physical and intellectual degeneration.

The leading cause of this ‘unwholesome deviation’ from basic health, according to Morel, is poisoning—addiction to narcotics and stimulants, such as alcohol and tobacco, which alternately depress and excite the human organism, and the consumption of polluted foods.

Nordau, writing forty years after Morel, adds another etiological factor to these ‘noxious influences’ in his Degeneration (1895)—‘residence in large towns.’

Under the conditions of modern, technological capitalism in these great ‘machines à vivre’ taking their model from Paris, Walter Benjamin’s ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’, man, according to Nordau, ‘breathes an air charged with organic detritus; he eats stale, contaminated, and adulterated food; he feels himself in a state of constant nervous excitement, and one can compare him without exaggeration to the inhabitants of a marshy district.’

‘No matter which party one may belong to,’ wrote Baudelaire in 1851, ‘it is impossible not to be gripped by the spectacle of this sickly population, which swallows the dust of factories, breathes in particles of cotton, and lets its tissues be permeated by white lead, mercury, and all the poisons needed for the production of masterpieces…; the spectacle of this languishing and pining population to whom the earth owes its wonders, who feel hot, crimson blood coursing through their veins, and who cast a long, sorrowful look at the sunlight and shadows of the great parks.’ … Baudelaire supplied his own caption for the image he presents. Beneath it he wrote the words: ‘La Modernité.’

— Walter Benjamin, “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire”, in The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (2006, pp. 102-3)

According to Nordau, these poisonous environmental conditions attendant on modern life in great cities produce a ‘fatigue’—an escalating ‘burnout’ of the human organism—an hysterical malady that places increasing wear and tear on the brain and tissue of each successive generation of human beings undergoing the ordeal of modernity.

‘The resistance that modernity offers to the natural productive élan of an individual is out of all proportion to his strength,’ Benjamin writes, and, as Nordau notices, in no place on earth were the nerves of human beings more frayed in the nineteenth century than in Benjamin’s capital of modernity itself—the epicentre of a political revolution that, in its continuing aftershocks, had become a social, cultural, and artistic revolution.

It was in this poisonous atmosphere of addiction, fashionable excitation, debased victuals, and political volatility that Charles Baudelaire was born and lived almost all of his brief, unhappy life.

Les Fleurs du mal are therefore not, as generations of English translators have so crudely rendered them, ‘The Flowers of Evil’.

In their exoteric aspect, the ‘allegorical image’ Baudelaire intended by that title, Les Fleurs du mal are emblems of malady, of a physical debility which is correspondent with a mental degeneration and vice versa.

As stigmatized derivatives of a primal, healthy type ‘before the Fall’ of modernity, it is only in this sense that these exotic, poisonous cultivars, weedy, unnatural blooms that Baudelaire has nursed in the hothouse of his soul—itself formed in the ‘artificial paradise’ of Paris—should be regarded as the products of an absolute immorality.

The skeletal Tree of Knowledge depicted by Rops—Science in its essence—unbandages man’s eyes from the blissful ignorance of God’s Nature.

When we enter the condition of modernity, we enter an artificial paradise, a fallen place of our own making, seductive and yet poisonous, in which the generations of Adam who work in the big cities bear the marks of Science’s guilty knowledge on their bodies and in their brains.

In its exoteric dimension, the title ‘Les Fleurs du mal’ might better be rendered, as I have chosen to do so, as ‘Toxic Blossoms’: these are creations of poisonous beauty that throw us back on the secondary paradox that arises from the primary fact of their being:—From whence does the Good, the True, the Beautiful really proceed?—from God, or from the Devil?

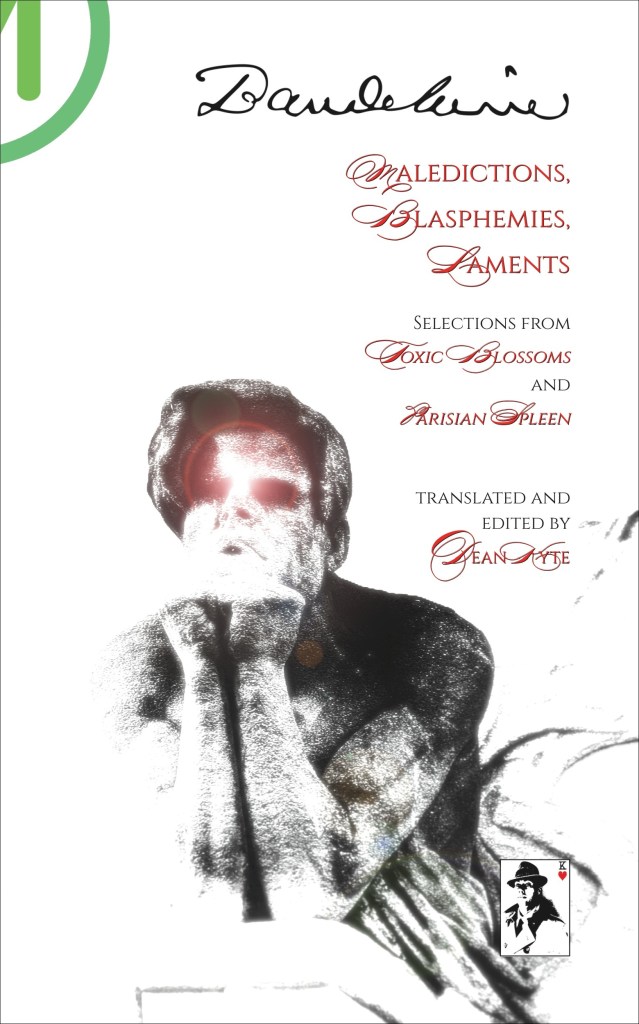

You’ve just been reading the first draft of a ‘chapterlet’ from the critical monograph on Baudelaire which will form the introduction to my forthcoming book of translations of Baudelaire’s poems and prose poems, Maledictions, Blasphemies, Laments: Selections from Toxic Blossoms & Parisian Spleen.

All 51 pieces in the book—33 poems, 17 prose poems, and 1 short story—are now complete.

As I put the final touches to the book, my last task is to complete a 10,000-word critical monograph on Charles Baudelaire in which I explain how, in his life and work, he both prophesies and embodies the decadence, decline, and degeneration of modern man that we are now experiencing all throughout the West—and particularly in the Anglosphere.

Pre-order your copy using the links below.